Wintertime was a time of travel in Sweden. The frozen riverbeds and bogs supplied virtual highways for sleighs and skiers. Summertime you where mostly restricted to climb the highest ”hole roads” (swe: Hålvägar), suitable only for sumpter horses. Much campaigning was done wintertime because of the ease of transportation. Also, the peasants were not needed to tend crops as much during winter. One drawback would be the lack of daylight, but at full moon and a clear sky the winter night is not very dark. Coping with cold is not as hard either. Firstly the Swedes of that time where used to be outdoors most of the time. Secondly, cold is mainly a factor when you stand still. Down to -15 to -20 degrees Celsius you will do good with just two woollen tunics as long as you are working or are in motion. As soon as you stand still you will need warmer clothes though, as your body will not generate warmth through being active.

Most things concerning winter campaigning is not about to clothes however, but of how you conduct yourself. Don’t stand in snow for long times. Stand on isolating pine branches. Don’t wear warm clothes on the move and get sweaty, put them on during breaks. Drink and eat regularly so the body have energy to keep itself warm you. Change wet socks right away, as getting wet is the best way to freeze. All these things were known even to medieval man as being outdoors was everyday life for them. They where probably more weather resistant and rugged then us normal modern weaklings and may have put up with a bit more discomfort then we are willing to endure. In Albrechts Bössor we are active the year round. Each year we stage a small one day winter march to test our gear to see that it will cope with winter conditions. This would have been vital for Swedish soldiers since, as stated above, many wars where fought wintertime. Thus we have found out some things that will be different from normal campaigning. So, there are some things one can get to make life in the wintertime easier.

Water

Although snow is water of a sort it is not always suitable for drinking. First of all, it cools you, and secondly its dry and don’t quench the thirst as good. For cooking, snow is excellent though, so there is no lack of water when in camp where there is snow. One problem that we encountered was that the water in the leather canteens froze. This resulted in that some of the canteens, that used a cork, was frozen shut and could not be opened at all. The one using a wooden plug could be pried open and the layer of ice that had formed inside hacked through with a dagger to get some drinking water. We recommend that canteens should be carried inside your clothes and let the body heat warm them, as is usual in modern days.

Winterclothing

Mittens and gloves

Mittens are a vital part of the winter gear. Hands get cold easily as the body draws heat from the extremities first to preserve it for vital organs. Five finger gloves where used as well as mittens and three fingered mittens. They could be in ordinary wool, felted wool, naalbinded, felted naalbinding or leather. No fur lined gloves have survived but it is very likely they have been around.

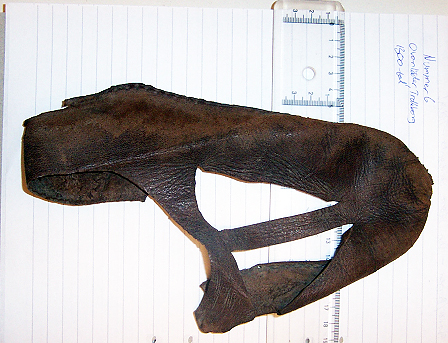

Socks

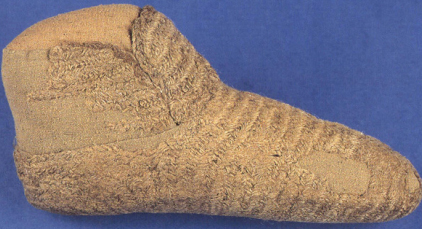

The feet are most often prone to getting cold while walking in snow so socks is rather essential. Maybe the medieval hikers made use of straw, stuffing it into oversized shoes, to keep warm. This is known to have been practised later on. However we have no evidence that they did so during the 14:th century. Naalbound socks however seems to have been in use.

Cloaks and coats

The cloak was used in Scandinavia in the 14th century maybe more then down on the continent. Coats also see good use, if we can judge from surviving documents from the time. The scholar Eva Andersson say coats and cloaks have been worn by both sexes even if cloaks seem to have been worn more by women than by men. Men seem to have preferred coats. Winter coats would have been lined for warmth, either with a thicker wool or with fur. Maybe furs have been worn as they where, that is, with the fur out. It is hard to tell from manuscripts as they do not use the terms the same way we do now. Pictures showing men wearing furs is picturing heathens in most cases and it is therefore not easy to use as reference on how ordinary people would dress. It seems to have been most common to wear the collar of the hood under the cloak/coat.

Hats

Although most hats used summertime will have been in use even wintertime the hood seems to be very popular during cold and harsh weather. It is also an almost perfect piece of clothing for this and its popularity is understood by all that has owned one. A lined hood, either with woollen cloth or with fur, will keep you warm and snug in winter. Anyone having had a lump of snow dumped inside the collar of your jacket when stirring a tree, will also know to appreciate the hood and its protecting collar. It also serves well to keep the neck warm as scarves don’t seem to be in use. As stated above it seems to have been practice to wear the collar of the hood under the cloak or coat, but over the tunic. This will save you from getting the collar blown up in your face when the wind comes. Other hats can include fur lined hats or just simple woollen ones. Fur lined hats are mentioned in contemporary documents and would have been worn even in summer. Hats with fur on the outside do not seem to have been popular though. On a pillar in the Linköping dome one can see hats on soldiers that are probably naalbound. Naalbound hats might have been more common than we know of now.

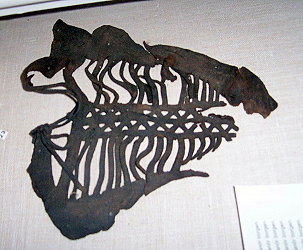

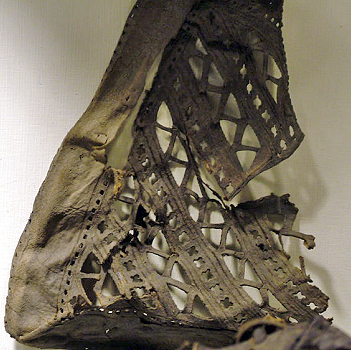

Shoes

Winter shoes differ from summer shoes mainly in that they need to be a bit bigger so that you can fit some kind of extra warming material in them, that is socks or such. An extra thick sole is also preferable to isolate from the ground. A shoe with a thick sole of cork has been found in Stockholm and is dated to around 14th century, as well as a sole with traces och naalbinding on it. Pattens is also of use in that matter. Maybe extra inner soles have been in use, but we know little of that. Traditional soles of birch bark was used in Sweden in old days, but if this habit dates back to 14th century we don’t know. They are excellent in keeping the feet warm though. Winter shoes should also have a bit of shaft on them to keep the snow out.

The winterdress reconstructed

These are some examples of the winter dress reconstructed and tested in outdoor activity wintertime. In general, they work as good, if not better then modern clothes.

Gloves

Gloves are vital since the hands get cold fast. Here are two pairs of naalbound gloves, three fingered and thumbed model, and one pair of three finger gloves made of hard felted wool lined with sheep fleece. The fleece lined gloves almost proved to warm. The felt, felted with earth, is very weather resistant.

The dress – Travel

On march, lighter clothing is worn since activity will keep you warm, especially if you carry a burden. The dress below shows a man on march. He wears a tunic (Swe: Kyrtil) and a super tunic (Swe: överkjortel) or Cote and Surcote. The air trapped between them will keep his body heat. Therefore they should not be to tight. He also sports a hood lined with fur. This one with black fur, being in fashion in late 14:th century. This hood was indeed very cosy in the chill winds. Also, he have double hose. These can be seen on illustrations where you see one pair rolled down. As always in winter clothing, the key here is layers. A pair of naalbound mittens and socks tops him of and makes him ready to travel the woods of King Albrecht’s Sweden.

The dress – reinforced

For taking breaks and standing still this dress in reinforced with a coat. The coat is made of rough felt, felted with earth to make it very weather resistant and water resistant. It is also lined with hare fur. This coat is very warm and will keep out water and wind like a charm. Combined with the hood it is an excellent winter garment.

A coat can also be lined with a thicker wool. Like this coat with a felt outside and a lining of a more ”airy” wool inside. The ”paired” buttons seems to have been more common on these kind of outer garments then on regular cotes.

The cloak

Although a bit out of fashion the cloak was used during the later 14th century, especially by women. Men carried them as well of course and they are rather good at keeping you warm. The drawback is that it is hard to work in them. As soon as you move too much, the warm air you have collected inside it escapes. Although, we used a cloak to test it. It is made from heavy wool and lined with a nice red and black striped wool. It is a rather heavy piece of clothing buttoned by three buttons. It is better to sleep in it than to work in it.

This article, written by Johan Käll, was previously published on our old webpage.