Some years ago we shot some film clips, and after a whole heap of lazy months, it has all been put together in a little movie. This is the first part. Enjoy!

Etikettarkiv: Scandinavia

The Hanseatic League in Stockholm

Background

After the war between Albrecht of Mecklenburg and Margareta (read more here), Albrecht and his son was imprisoned at castle Lindholmen in the region of Skåne in southern Sweden. In July 1394, after lengthy negotiations, it was agreed that the two Mecklenburgers should be set free for a ransom of an immense sum of money, equivalent to about 8 000 kilos (more than 17 600 lbs) of pure silver. In short, they were to be released for three years, in which they had to come up with the money, and the city Stockholm was to act as a kind of deposit. Stockholm was the only city in Sweden still controlled by the Germans and hence a thorn in Margareta’s side. During those three years, Stockholm was to be superintended by a group of Hanseatic cities (Königsberg, Elbing, Thorn, Danzig, Reval, Greifswald, Lübeck and Stralsund), as the cities had agreed to act as guarantors for Albrecht. For their troubles, Margareta should pay them an annual sum of 2 000 mark for the three years they administered Stockholm. Also, the cities Rostock and Wismar (the heartland of the Mecklenburg dynasty) should help out with considerable sums of money – 1 000 mark per year.

The mission

Preparations

The 20th of May 1395 the cities met in the neighboring fishing towns Skanör and Falsterbo, at the southwesternmost tip of Sweden and they agreed about their respective contributions to the mission, in wider terms. Here, they also came to terms with Margareta that the king and his son Erich were to be set free the 29th of September. It was agreed that Greifswald, Stralsund and Lübeck should send half of the personnel, equipment and provisions needed. The Prussian cities (the five remaining of the eight) should send the other half.

As an aside, 1395 is a year where the so called Vitalian brotherhood (a group of pirates) starts to take up more and more of the Hanseatic League’s agenda; in September it is decided that a peace keeping/pirate hunting fleet consisting of 11 ships and 1 000 men at arms is to be set up until 1396 to address the piracy problem. 1396 the pirates are mentioned in almost every meeting held by the Hanseatic League, which gives an impression of the situation in the Baltic region.

The Skanör-Falsterbo agreement above states that the eight cities in total should send the following personnel and equipment to take control of Stockholm:

- 80 good men at arms in full armour (in this case this included torso protection other than chainmail)

- 60 good crossbowmen with their weapons and including equipment

- 12 barrels of crossbow bolts

- 8 stone guns (bigger cannons)

- 2 lead guns (smaller cannons/hand guns)

- “A lot of gunpowder, which is needed for that” [the guns]

- 60 good crossbows including levers and windlasses

- Two good gunnery masters

- Two crossbow makers

In addition, the cities sent large amounts of food; in short, everything that was needed to survive was to be shipped to Stockholm, including different food stuffs and tools.

About two months later, in the middle of July, the cities met in the Teutonic order castle of Marienburg/Malpork, where more exact guidelines for the mission are drawn. The troops shipped to Stockholm from the Prussian cities (Königsberg, Elbing, Thorn, Danzig, Reval) are:

- 38 men at arms

- 22 crossbowmen

They bring

- 8 guns of different types, including powder, lead for making shot and peripheral equipment

- 1 gunnery master

- 1 crossbowmaker

- 30 crossbows

- 4 barrels of crossbow bolts

- Peripheral equipment for the crossbows

The soldiers

Personal equipment

In the Marienburg meeting it was stipulated that each soldier should be equipped according to the following lists:

Each crossbowman should have:

- 60 good bolts with tips

- 3 crossbows (!) – one big, one middle sized and one small

- A chainmail

- A “chest” – probably a coat of plates

- A mail coif

- A iron hat

- Plate gauntlets

- A shield

Each man at arms should have:

- A “whole plate armour and what belongs to it”:

- A hood (most likely a helmet)

- A coat-of-plates

- Arm protection made of leather

- A “vorstal” – probably lower arm protection made of steel

- Leg protection

- A shield

Curiously, nothing is mentioned of which weapons a man at arms should bring. Perhaps it didn’t matter, as long as they were armed. I have found no similar lists for Stralsund, Greifswald and Lübeck, but most likely those cities sent a similar number of soldiers with similar equipment.

Loyalty

The soldiers going to Stockholm had to swear a sacred oath when signing up for service:

Dys yst der wepenere unde schuczen yet unde buchsenmeystere unde bogenere. Wir sweren und geloben uch, borgermeisteren, ratmannen unde der ganczen gemeyne der stede Thorn, Elbing, Danczik unde Revele, daz wir hern Hermanne van der Halle, euwirme houbtmanne, und unsern eldesten getruwe und gehorsam will zin in bewarynge, in wache, in were des huses, veste und stat Stokholm, unde in alle anderen dingen, des uns van in bevolen wirt; unde van dannen nicht to scheydende, ee ir uns orlob gebit unde andere in unse stat sendit. Das en wille wir nicht lassen durch lib noch durch leyt, daz uns Got zo helfe unde dy heylighen.

This is roughly translated into:

This is the oath of the men at arms, the crossbowmen, the gunnery masters and the [cross?]bowmakers. We swear and promise you – the mayors, the council and all the common people of the cities Thorn, Elbing, Danzig and Reval, that we will be true and obey herr Hermann van der Halle, our noblest commander, when it comes to guarding and caring for the houses, castle and city of Stockholm, and in all other things he will command us; and therefore not to let anyone in [to Stockholm] without permission, in good times or in bad, so help us God and the Saints.

Pay, benefits and conditions

The tour of duty for the soldiers going to Stockholm was to be 18 months long, as suggested by a meeting the 19th of August, 1395.

The soldiers from the Prussian cities were paid both in fabric and in money. The men at arms was to be paid in 6 ells (1 ell = nearly 60 centimeters) of black and brown fabric (probably 2 ells wide) from Dendermonde (in Flanders), from which they should make “wide coats and hoods”, where the black should be on the right side and the brown on the left. The crossbowmen should have hoods in the same colors, plus parcham (a fabric consisting of both linen and cotton) for their jacks/gambesons. The pay also consisted of 5 marks in coin per year for the crossbowmen and 10 marks per year for the men at arms. It is not clear whether similar conditions applied to the contingents from Stralsund, Lübeck and Greifswald, even though it is probable.

In excess of this, the soldiers would probably have had free food, drink and lodgings. But like always, it seems the pay for the contingent was too little and too late. In comparison to other missions (i.e. on peace keeping ships) the pay wasn’t exactly good. In April 1396 a League meeting in Marienburg states that men at arms that goes on the peace ships without their own armour shall have 1/3 of one Mark each week. If we presume that the peace keeping mission lasted for a year (which it probably didn’t), the participating men at arms would earn more than 50% more per year than their colleagues in Stockholm. On the other hand, the peace keepers didn’t receive any fabric, but this doesn’t cover the difference.

That might be why the superior commander of the Stockholm mission, Hermann van der Halle, made complaints about “uncomfortable” individuals in the force; it could have something to do with the talks at a League meeting the 31st of December, 1396, where the gathered representatives decide to postpone the question of “pay for the men at arms that have been posted in Stockholm this year” to an upcoming meeting.

Food

It seems the garrison commander had trouble making ends meet. Van der Halle sent frequent letters to his superiors asking for the most basic commodities to be shipped from Germany, which indicates the contingent couldn’t easily get hold of locally produced food; for some reason the force couldn’t even use the mills in Stockholm and had to grind their grain to flour via a hand mill.

This, among other things, were ordered from Germany to be delivered to the garrison: Apples, honey, onions, beer, pork, many different kinds of fish, bread, turnips, vinegar, salt, mustard, different kinds of oil (which could also have been used as fuel for lanterns), flour, malt, hops, peas, horseradish, apples and garlic.

Among the finer foods (probably reserved for the commanders) can be found: rice, almonds, raisin, wine and spice.

The posting

Arrival

The contingent, commanded by the Danzig council member Hermann van der Halle, who was appointed supreme commander of the mission, reached Stockholm and took control over it the 31st of August, 1395. The day after that, the commander of the Stralsund contingent, Magnus von Alen, arrived in Stockholm with his men. Lübeck also seem to have sent a commander – Jordan Pleskow (who maybe rather wanted to stayed at home in his house on Johannisstraße 20 in Lübeck – we’ll never know). A week later, the 8th of September, the cities promised the Stockholm burghers the same freedoms as they had under the reign of King Albrecht, and the burghers – in turn – promised to be true to the trustees responsible to administer the pawned city.

The keepers of the castle, which consisted of Albrecht supporters, among others Hinrike von Brandis and Otto von Peckatel, had been informed of the turning of the tide beforehand; the Hanseatic League wrote them a letter a month before van der Halle and his troops arrived in Stockholm. Von Brandis and von Peckatel handed the city over to van der Halle without much of a fuss.

We are presented with information that paints a picture of Stockholm castle in disrepair, and probably the soldiers were put to work to repair everything, including the lodgings that had been built by private persons in the castle. The inhabitant of said lodgings – the duke Johann von Mecklenburg (a relation to King Albrecht) asked van der Halle’s permission to remain, something he was denied.

The soldiers had nevertheless to undertake what was most likely extensive renovations; the walls and roof of the castle was in a sorry state, and the cities demanded that the renovations were kept cheap. Also, the old castle commander “borrowed” a lot of kitchen equipment and a stone gun, which needed to be replaced. To assure that the borrowed gun shouldn’t be used against the castle by the leaving force, van der Halle decided to buy it from the leaving Albrecht supporters.

A less than desirable task

Hermann van der Halle didn’t seem too happy with his task. His letters back to his superiors are full of new requisitions as the victuals always ran out. Already the 19th of September, 1395, the council of Marienburg addressed van der Halles requisition for onions, garlic, herbs, fruit, honey, cod, beer, wine – and “6 or 8 big hounds, that we need so well for the castle”. Seven days later the council at Marienburg addressed a second requisition of malt, barley, more beer and wine, flour, fish, vinegar, onions, more dogs, two big ships to defend against the Vitalian brotherhood, wooden boards, (lots of) shovels and brick trowels.

In June 1396 we learn that Stockholm castle had been divided between the Stralsund forces of Magnus van Alen and the forces of Hermann van der Halle, where the Stralsunders were using the tower for their needs and the other troops occupied the courtyard (probably in the buildings erected by duke Johann von Mecklenburg) plus a cellar belonging to the keep, as they had agreed on that this was the best way to defend the castle.

Risky business

However, it seems the stay in Stockholm wasn’t only hard work; the Vitalian brotherhood was increasingly seen in and around the city – both as visitors (even as guests of the Stockholm council during wintertime, something that worried van der Halle) and as pirates. In April 1396, the cities asked van der Halle to send what troops he could spare to the peace keeping mission against the brotherhood being set up by the League.

In June he reported that ”a good hundred” members of the brotherhood, that had spent the winter in Stockholm, finally set off for Russia under the command of eight commanders in eight freight ships and with ”gunner boats”. Van der Halle made them promise not to go after the Hanseatic merchants or cities in Livonia before they left.

In August the same year, van der Halle reported several incidents involving the pirates and merchant sailors; the situation was clearly becoming more and more dangerous for the Stockholm detachment.

Furthermore, some things indicate that the commander didn’t quite trust all of his men, as he asked his superior’s permission to send some of them home: ”if they don’t please me, I want to [be allowed to] tell them: ’Go home!'”.

It seems Hermann van der Halle was also worried about the agents of Margareta; the queen invited him to meetings several times during 1396, but he never left his post. Even when the queen sent her envoy, Sten Bengtsson, to visit Stockholm, he had to announce his visit some day ahead to be let inside the gates. The queen’s envoys also demanded (according to their view of the peace treaty) that he should open the gates to 300 Swedish burghers that had been banished from the city due to their lacking loyalty to King Albrecht. Van der Halle asked his superiors for orders concerning this, but had a hard time stopping the said burghers from coming and going to the city.

By this, we can assume that the soldiers of the League was in a constant state of readiness.

Relief

Hermann van der Halle’s successor, Albrecht Russe, arrived in Stockholm in the beginning of October 1396, accompanied by an experienced old fighter and diplomat, sent by the Elbing council. His name was Claus Wulf and he had commanded soldiers since at least 1386. Likely he was sent to command the Elbing contingent, under the command of Albrecht Russe. Russe assumed command over the garrison and no sooner, Hermann van der Halle borrowed 100 marks from Russe and left in the first ship available. More than a year later he is still struggling to get the League to pay him what it owed him for his expenses in Stockholm.

If Albrecht Russe thought he would have an easy time, he was mistaken. He had to deal with the same troubles that pestered van der Halle. He hadn’t enough men, although he had too much men to feed them properly, he had to address the issue with “uncomfortable” and probably bored and restless personell and he was working at a place where he was less than welcome by the populace and by the pirates.

However, he seems to have had his ear to the ground, as he picked up a subtle warning about events waiting to occur during the summer of 1397. When commanding Stockholm castle, Hermann van der Halle had feared that a Swedish nobleman named Algot Magnusson had struck some kind of a deal with the Vitalian brotherhood. His fears seems not to have been ungrounded, as a man came to Russe, warning him of an imminent danger. The 28th of June, a big fleet of the brotherhood arrived in Stockholm, issuing demands. One can imagine the commotion in the castle when the 100 or so soldiers at some hours notice tried to ready the defenses against a force that was 1 200 men strong. Later, Russe told his superiors that he and his men had been nowhere close to ready or strong enough, and that the city would have fallen if the brotherhood had attacked.

In January 1398, Russe complained that Margareta didn’t send money for the upkeep of Stockholm, as agreed. At the same time he asked for provisions (as always) and to be relieved of his post the upcoming easter. In the agenda of a late February League meeting the participants urge that Rostock and Wismar should pay what they owe for the keeping of Stockholm. Money was, as usual, a problem.

In May 1398 a meeting at Marienburg decided that every city involved in the mission should send 3,5 Mark worth of victuals per soldier from the city in question – a grand total of 300 Mark. This is a bit interesting as it gives us an approximate number of the garrison. At this time it seems the force in Stockholm was about 85 men strong. Maybe some of the ”uncomfortable” elements were sent home?

After this, the annals of the Hanseatic League doesn’t mention the Stockholm garrison much. The times Stockholm are mentioned, it is regarding its surrender to Margareta.

Aftermath

During the spring of 1398, Margareta corresponds with the cities about her accession of Stockholm. The 12th of August she states that if King Albrecht hasn’t payed his ransom by the 24th, she will ask him to surrender Stockholm to her. The 29th of August, she – along with her son Bogislav (now king of Sweden) – grants Stockholm all of its previous rights; as history tells us, the king couldn’t come up with the money. The contingent from the Hanseatic League leaves the city the 29th of September and Margareta takes over. The mission is accomplished and the soldiers return home – or sets off to find the next filled purse, perhaps as part of the ever ongoing war against the Vitalian brotherhood.

The supreme commanders from Prussia

Hermann van der Halle

When the cities’ troops first arrived in Stockholm – in August 1395, they were supervised by the Danzig council member Hermann van der Halle, as mentioned above. He was sworn in as hovetman the 1st of August, where he specifically asked that his mission as commander over Stockholm should last no longer than a year.

He had the responsibility to keep Stockholm safe, which was easier said than done. Hermann van der Halle’s letters often include reminders to his superiors that he was promised to be relieved of his post after one year; it is clear that he is not very happy in Stockholm. Maybe it had something to do with the people he was forced to work with; in July, 1396 he thanked his superiors for the long asked for permission to send “uncomfortable” individuals home. Probably he was referring to members of the Thorn contingent – he made complaints about them at a League meeting in March 1397.

The 15th of June 1396, his supervisors sent him an eagerly awaited letter – he was to be relieved – as promised – by the Thorn council member Albrecht Russe. The 3rd of September he seemed somewhat anxious to learn that Russe had fallen ill in Lübeck. In the end of the same month, van der Halle himself fell ill, and as he experienced that he was of no use to the garrison, he desperately asked his superiors to send another commander as soon as they were able.

He seems to have pulled through, though, as he was present at a League meeting in Marienburg, the 31st of December, 1396.

Albrecht Russe

The Thorn council member Albrechts Russe (or “Albrecht Rusze” as he spelled it himself – an indication of his perhaps Russian descent) was appointed council member of Thorn 1393. This might well have been his first commission, where he acted as a representative for the city at various League meetings. During his career he also acted as a bailiff, mediator and solicitor, as well as councillor and mayor in the same city. He acted as a diplomat during various diplomatic postings, and was probably also a shipowner responsible for Thorn’s trading relations with Poland. A heavy weighter, no doubt.

In 1396 it is decided that he is to succeed the commander of the Stockholm garrison, Hermann van der Halle. The 14th of September 1396, Russe sends word that he plans to depart from Wismar to Stockholm the 29th of September. It is probable that he arrived in Stockholm less than a week later, which means his predecessor could take the first boat home and the heck out of Dodge during the first days of October.

Russe assumed command at the most critical period of the Hanseatic administration of the Swedish capital. The evening of the 29th of June, 1397, a fleet of 42 ships and 1 200 men, commanded by “Otto von Peckatel [former commander of the Stockholm garrison], Sven Stur, Crabbe, Egkart Kale, Kawle and other commanders that I do not know” reached Stockholm. It was a fleet belonging to the Vitalian brotherhood. It had sailed from Gotland where King Albrecht’s son Erich had put up his headquarters, along with several notable nobles – among others the duke Johann von Mecklenburg who was evicted from his house in Stockholm castle in 1395. This means that Erich von Mecklenburg took active part in the piracy that Margareta, the Teutonic order and the Hanseatic league was trying to thwart, even though he was released on bail. Perhaps this was his way to raise money for the ransom. Either way: talk about stirring the pot…

Russe sent a letter to his superiors recounting what had taken place that evening. Its contents were read out and addressed at a League meeting in Danzig the 2nd of July, three days later.

The two sides met at a small isle outside Stockholm to parlay. The fleet commanders demanded to be let inside the city, but the officials of Stockholm refused. The fleet then demanded 10 000 loaves of bread and 20 “last” (= 200 plus barrels = more than 43 000 liters) of beer. The commanders of Stockholm refused a second time, and the fleet commanders asked to buy the commodities they needed. Again they are refused; the Stockholm officials suspected treason as Albrecht Russe had received a warning some time earlier.

He tells his superiors:

A good man came to me and told me to guard the castle well – or be in dire hardship. Then I told him: ”My dear friend, can’t you speak your mind?” He said that he couldn’t tell me. He kneeled, and put two fingers on a brick, and spoke thus: ”Brick! I tell you this, as God and the Saints help me: Stockholm is betrayed!” He rose and reached his arms towards the sky and spoke: ”So help me God until my last day – what I have sworn here is the truth!” He would tell me nothing more.

After this, Russe asked for more provisions and reinforcements (“good people”) as he believed Stockholm to be in real danger. However, the fleet departed and left Stockholm alone. The League responded by ordering that one of the gates in Stockholm should be walled shut, perhaps as part of the defenses against the brotherhood.

Like his predecessor, Albrecht Russe constantly asked to be relieved, which makes you wonder what kind of a place Stockholm was. In late summer 1397, the League sent him a letter and told him that he, in time, was going to be relieved from his post by a representative from Elbing. It is uncertain if he ever was relieved or if he remained on his post until the mission in Stockholm ended.

Early artillery in Scandinavia

This article, written by the archaeologist Sven Rosborn, tell the story about early artillery in our part of the world.

Timeline of Swedish politics 1306-1412

History during the 14th century can be quite confusing, and it’s more or less impossible to write a chronology in common prose. That is why we have made this timeline. Hopefully it will help you out when trying to understand the different schemes, alliances and events that took place during the period.

Click the tiny image to make it (a lot) bigger.

Read the 14th century history of Sweden in more detail in these pages:

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 1 – The beginning

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 2 – The struggle of the lawmaker

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 3 – The age of the king

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 4 – Defeat and union

This page may also be helpful:

Family tree of Swedish royals during the 14th century

Coping with winter

Wintertime was a time of travel in Sweden. The frozen riverbeds and bogs supplied virtual highways for sleighs and skiers. Summertime you where mostly restricted to climb the highest ”hole roads” (swe: Hålvägar), suitable only for sumpter horses. Much campaigning was done wintertime because of the ease of transportation. Also, the peasants were not needed to tend crops as much during winter. One drawback would be the lack of daylight, but at full moon and a clear sky the winter night is not very dark. Coping with cold is not as hard either. Firstly the Swedes of that time where used to be outdoors most of the time. Secondly, cold is mainly a factor when you stand still. Down to -15 to -20 degrees Celsius you will do good with just two woollen tunics as long as you are working or are in motion. As soon as you stand still you will need warmer clothes though, as your body will not generate warmth through being active.

Most things concerning winter campaigning is not about to clothes however, but of how you conduct yourself. Don’t stand in snow for long times. Stand on isolating pine branches. Don’t wear warm clothes on the move and get sweaty, put them on during breaks. Drink and eat regularly so the body have energy to keep itself warm you. Change wet socks right away, as getting wet is the best way to freeze. All these things were known even to medieval man as being outdoors was everyday life for them. They where probably more weather resistant and rugged then us normal modern weaklings and may have put up with a bit more discomfort then we are willing to endure. In Albrechts Bössor we are active the year round. Each year we stage a small one day winter march to test our gear to see that it will cope with winter conditions. This would have been vital for Swedish soldiers since, as stated above, many wars where fought wintertime. Thus we have found out some things that will be different from normal campaigning. So, there are some things one can get to make life in the wintertime easier.

Water

Although snow is water of a sort it is not always suitable for drinking. First of all, it cools you, and secondly its dry and don’t quench the thirst as good. For cooking, snow is excellent though, so there is no lack of water when in camp where there is snow. One problem that we encountered was that the water in the leather canteens froze. This resulted in that some of the canteens, that used a cork, was frozen shut and could not be opened at all. The one using a wooden plug could be pried open and the layer of ice that had formed inside hacked through with a dagger to get some drinking water. We recommend that canteens should be carried inside your clothes and let the body heat warm them, as is usual in modern days.

Winterclothing

Mittens and gloves

Mittens are a vital part of the winter gear. Hands get cold easily as the body draws heat from the extremities first to preserve it for vital organs. Five finger gloves where used as well as mittens and three fingered mittens. They could be in ordinary wool, felted wool, naalbinded, felted naalbinding or leather. No fur lined gloves have survived but it is very likely they have been around.

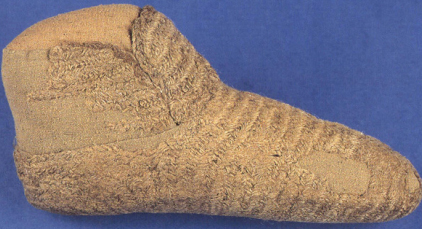

Socks

The feet are most often prone to getting cold while walking in snow so socks is rather essential. Maybe the medieval hikers made use of straw, stuffing it into oversized shoes, to keep warm. This is known to have been practised later on. However we have no evidence that they did so during the 14:th century. Naalbound socks however seems to have been in use.

Cloaks and coats

The cloak was used in Scandinavia in the 14th century maybe more then down on the continent. Coats also see good use, if we can judge from surviving documents from the time. The scholar Eva Andersson say coats and cloaks have been worn by both sexes even if cloaks seem to have been worn more by women than by men. Men seem to have preferred coats. Winter coats would have been lined for warmth, either with a thicker wool or with fur. Maybe furs have been worn as they where, that is, with the fur out. It is hard to tell from manuscripts as they do not use the terms the same way we do now. Pictures showing men wearing furs is picturing heathens in most cases and it is therefore not easy to use as reference on how ordinary people would dress. It seems to have been most common to wear the collar of the hood under the cloak/coat.

Hats

Although most hats used summertime will have been in use even wintertime the hood seems to be very popular during cold and harsh weather. It is also an almost perfect piece of clothing for this and its popularity is understood by all that has owned one. A lined hood, either with woollen cloth or with fur, will keep you warm and snug in winter. Anyone having had a lump of snow dumped inside the collar of your jacket when stirring a tree, will also know to appreciate the hood and its protecting collar. It also serves well to keep the neck warm as scarves don’t seem to be in use. As stated above it seems to have been practice to wear the collar of the hood under the cloak or coat, but over the tunic. This will save you from getting the collar blown up in your face when the wind comes. Other hats can include fur lined hats or just simple woollen ones. Fur lined hats are mentioned in contemporary documents and would have been worn even in summer. Hats with fur on the outside do not seem to have been popular though. On a pillar in the Linköping dome one can see hats on soldiers that are probably naalbound. Naalbound hats might have been more common than we know of now.

Shoes

Winter shoes differ from summer shoes mainly in that they need to be a bit bigger so that you can fit some kind of extra warming material in them, that is socks or such. An extra thick sole is also preferable to isolate from the ground. A shoe with a thick sole of cork has been found in Stockholm and is dated to around 14th century, as well as a sole with traces och naalbinding on it. Pattens is also of use in that matter. Maybe extra inner soles have been in use, but we know little of that. Traditional soles of birch bark was used in Sweden in old days, but if this habit dates back to 14th century we don’t know. They are excellent in keeping the feet warm though. Winter shoes should also have a bit of shaft on them to keep the snow out.

The winterdress reconstructed

These are some examples of the winter dress reconstructed and tested in outdoor activity wintertime. In general, they work as good, if not better then modern clothes.

Gloves

Gloves are vital since the hands get cold fast. Here are two pairs of naalbound gloves, three fingered and thumbed model, and one pair of three finger gloves made of hard felted wool lined with sheep fleece. The fleece lined gloves almost proved to warm. The felt, felted with earth, is very weather resistant.

The dress – Travel

On march, lighter clothing is worn since activity will keep you warm, especially if you carry a burden. The dress below shows a man on march. He wears a tunic (Swe: Kyrtil) and a super tunic (Swe: överkjortel) or Cote and Surcote. The air trapped between them will keep his body heat. Therefore they should not be to tight. He also sports a hood lined with fur. This one with black fur, being in fashion in late 14:th century. This hood was indeed very cosy in the chill winds. Also, he have double hose. These can be seen on illustrations where you see one pair rolled down. As always in winter clothing, the key here is layers. A pair of naalbound mittens and socks tops him of and makes him ready to travel the woods of King Albrecht’s Sweden.

The dress – reinforced

For taking breaks and standing still this dress in reinforced with a coat. The coat is made of rough felt, felted with earth to make it very weather resistant and water resistant. It is also lined with hare fur. This coat is very warm and will keep out water and wind like a charm. Combined with the hood it is an excellent winter garment.

A coat can also be lined with a thicker wool. Like this coat with a felt outside and a lining of a more ”airy” wool inside. The ”paired” buttons seems to have been more common on these kind of outer garments then on regular cotes.

The cloak

Although a bit out of fashion the cloak was used during the later 14th century, especially by women. Men carried them as well of course and they are rather good at keeping you warm. The drawback is that it is hard to work in them. As soon as you move too much, the warm air you have collected inside it escapes. Although, we used a cloak to test it. It is made from heavy wool and lined with a nice red and black striped wool. It is a rather heavy piece of clothing buttoned by three buttons. It is better to sleep in it than to work in it.

This article, written by Johan Käll, was previously published on our old webpage.

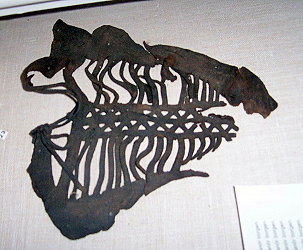

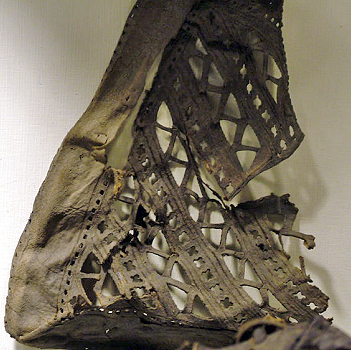

Some shoes from medieval Sweden

This is merely a a list of some photographs of shoes we have encountered in different museums in Sweden. The shoes used in Sweden was not very different from shoes in the rest of Europe, at least not that we can see from archaeological evidence. In the salary for people working in farms during 14th century usually three pairs of shoes and a pair of pattens a year was included, along with food and boarding.

Boots

Some rough shoes for use in less civilised areas.

Fancy shoes

No reason you can not have fancy shoes just because you live in a barbaric country is there? The Swedes were trying to be part of continental fashion too.

Other shoes

Written by Johan Käll & Peter Ahlqvist

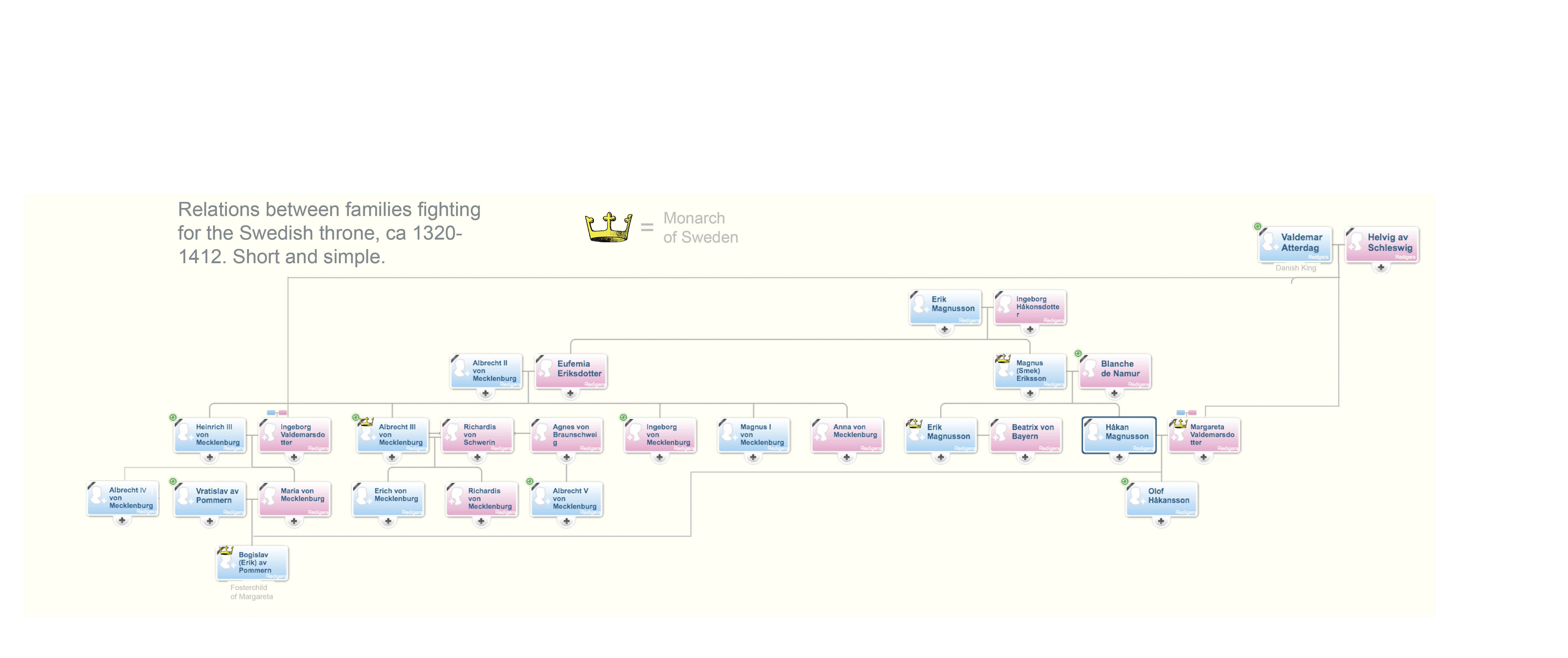

Family tree of Swedish royals during the 14th century

When you are trying to understand the battle of the crown in 14th century Sweden, you will pretty soon be quite mixed up in relations. This family tree is simplified to show which people held keep positions in the struggle.

In short, ”our” king Albrecht was king Magnus Eriksson’s sister’s son, which meant he could make a (kind of) legitimate claim for the throne. Margareta Valdemarsdotter was married to Håkan Magnusson, Magnus Eriksson’s son, which meant her son Olof Håkansson could make a (kind of) legitimate claim for the throne. When he died at the age of 17, Margareta adopted her sister Ingeborg Valdemarsdotter’s grandson, Bogislav of Pomerania (who was also the grandson of ”our” Albrecht’s brother), which meant that he could claim the throne. Legitimate? Well, you tell me… That was the short version. The more elaborate story begins in this post.

We have chosen to be extra specific when it comes to king Albrecht’s immediate family (his name on this image is Albrecht III von Mecklenburg). Other characters of note is the strongheaded duchess Ingeborg Håkansdotter, mother of king Magnus Eriksson and self-appointed ruler of the realm, and her husband, the duke Erik Magnusson, who was put in a tower to starve to death by his brother Birger. Also, there is Håkan Magnusson – king of Norway and faithful son of king Magnus (not to mention king Erik Magnusson – the unfaithful son of king Magnus). Also, have a special look at the foster relation between Bogislav of Pomerania (to the far left) and his grandmother’s sister – queen Margareta of Denmark; the duo ruled Sweden after the defeat of king Albrecht, and when Margareta died, Bogislav ruled the entire Kalmar union.

Click the image to view a bigger version. We apologize for the colors, which look like they have been stolen from a nursery from the 1960’s…

This page might make more sense together with the following pages:

Timeline of Swedish politics 1306-1412

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 1 – The beginning

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 2 – The struggle of the lawmaker

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 3 – The age of the king

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 4 – Defeat and union

Who was Albrecht of Mecklenburg?

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 4 – Defeat and union

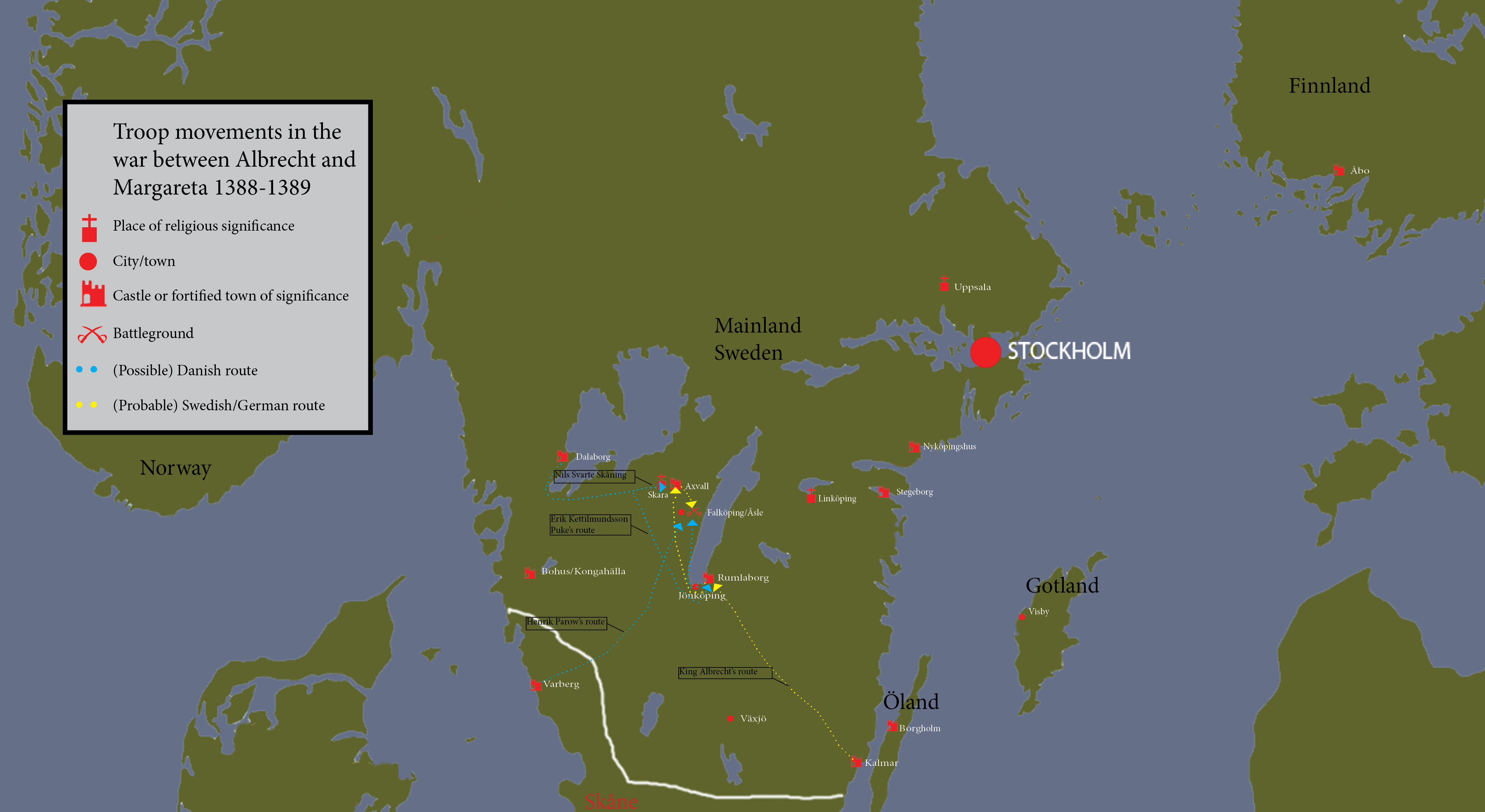

Winds of war

After the meeting at Dalaborg, Margareta starts to gather an army to fight the king, But Albrecht is not sitting idle. He makes the burghers of Stockholm renew their oath of fealty to him and departs for Germany to muster troops. Margareta is ahead of him, and with an army of Swedes her supporters besiege the stronghold of Axvalla. It is too strong to take by storm, and a long siege lead by Nils Svarte Skåning begins. The main part of the army marches on, under the command of Erik Kettilsson Puke (whose name has got nothing to do with throwing up).

Around new year 1389 Albrecht returns to Sweden with a host of men. He disembarks at Kalmar and march on Axvall. On the way there, he passes the south peak of lake Vättern, and manage to liberate the besieged Rumlaborg. When he reaches Axvall he also receives word that a Danish army, under the command of his old retainer Henrik Parow has been marching from Halland and is about to join the army of Erik Kettilsson Puke. Albrecht turn south to face the two armys, and the 24th of february they meet outside the village of Åsle, in the vicinity of Falköping.

The chronicler Detmar describes it like this:

In deme jare Cristi 1389, in sunte Mathias dage, was grot strid in Sweden bi Axewalde. De koninghinne van Norwegen hade dar sand wol vifteynhundert gewapent. Der hovetman was en riddere, de heet her Hinrik Parowe.

On this day of Christ 1389, in saint Matthew’s day, it was a great battle in Sweden by Axvall. The queen of Norway had sent a good fifteenhundred armed. The commander was a knight that was called Henrik Parow.

Henrik Parow’s troops take a defensive position flanked by a mountain and a marshland, which also stretches in front of his lines. Albrecht is eager to engage, and he is certain of victory; his host consists of glorious German knights and trained mercenaries. But everyone is not as sure as he is. Tradition tells us that an old knight called Tyke Olofsson asked the king to refrain from attacking, or at least try to negotiate the marshland before charging. ”We do not want to fight the Dane this day – it won’t do us any good.” he concluded, but the king wouldn’t listen. Even though some of his men weren’t ready, he lead his knights, including the bishop of Skara, his cousins and the counts of Ruppin and Holstein, on a charge across the frozen land and at first he was very successful: he ”conquered two banners”. But the battle would not go his way. One of his commanders, Gerhard Snakenborg, turned and fled the battlefield with 60 riders, and others is said to have stuck in the boggy ground.

In less than two months, through snow and during very harsh conditions, king Albrecht’s army marched over 300 kilometers – and had time to stop and liberate Rumlaborg before fighting at Åsle

The king was taken captive along with his son, prince Erich, and as they were taken from the field of battle by their captors, they passed Tyke Olofsson. The king cried out to him: ”Old man! Old man! Why didn’t I listen?” The battle of Åsle is a decisive victory for the rebels, but their commander, Henrik Parow, is killed. When the queen learns of the victory she rides to Bohus where she and her supporters celebrate their victory. The king and his son are eventually taken to Skåne and the castle of Lindholmen, where they are being held captive.

German resistance

Even though Margareta managed to beat her enemy at the battlefield, her fight for dominion of Sweden was far from over. Although she conquers Kalmar, Rumlaborg and Axvall, Stockholm is still in German hands, and the burghers of the city refuse to give up the fight. They are being supported by the Hansa, which send warships to commandeer ships belonging to the supporters of Margareta. They also bring food and soldiers to the besieged Stockholm. On a different note, these ships, crewed by knights, burghers, soldiers and peasants, according to Detmar, later cause much trouble on the Baltic sea as pirates (so called Vitalianer). As they are allowed to enter the harbours of the Mecklenburgish Wismar and Rostock, other Hansa cities, which suffered economic losses due to pirate attacks, started to lose interest in the conflict between the Mecklenburgish dukes that supported Albrechts and the queen Margareta. Nevertheless, some of the Hanseatic towns, Rostock among some others, make alliances with noblemen and other cities to try to force Margareta into releasing Albrecht; among other things they try to enforce a trade embargo against Margareta. But their efforts are of little use. Some, like the old Albrecht-loyal knight Vicke van Vitzen even sells his estates to Margareta and swear loyalty to her. He was not the only one to do so.

The aggressive Vitalianer pirates put a hamper on trade in the Baltic sea. Many ships were just anchored as the risk of sailing was too great

In 1393 the conflict is putting a big hamper on trade in the Baltic sea, not least because of the Vitalianer. Margareta met with representatives from the Hansa and king Albrecht’s nephew Johann in Falsterbo at the end of September. At this meeting it was agreed that Albrecht and his son should be let free from captivity for a couple of years, until the parties had reached an acceptable agreement. As security, the city of Stockholm was to be handed over to four honest men, which should let Margareta occupy it if the king refused to go back to captivity after the said time.

The war goes on – but so does the negotiations

In July 1394 everyone finally seemed to agree. The king and his son had been imprisoned for more than five years, and the king himself probably knew that his days as king of Sweden were numbered. He was to be released against a huge ransom of 60 000 marks of silver (the old king Magnus bought the entire province of Skåne for about half as much in the 1330’s), and if that sum wasn’t paid back in six months, the king and his son should return into captivity, or the queen would be entitled to occupy Stockholm. At the same meeting, Margareta and the Hansa also agreed on taking actions against the Vitalianer, as they were still a serious problem for great parts of northern Europe. During the 1390’s tremendous efforts were put on ridding the Baltic sea from pirates. Several fleets with several thousand men hunted the Vitalianer and drove them from whatever harbors the controlled.

The final negotiations for the king’s release took place at Lindholmen were king Albrecht and his son had been spending their time since the defeat at Åsle. The 26th of September 1395 it is decided that Albrecht and his son should be released for a period of three years (until the 29th of September 1398), during which time they should try to raise the enormous ransom. If he succeeded, he wasn’t allowed to wage war on Margareta for at least a year. If he didn’t succeed, he could go back to prison but break the peace in nine weeks, or he could simply let Margareta have Stockholm and the peace should be everlasting. Albrecht was released in Helsingborg at the end of September 1395, about a month after Stockholm was entrusted to the Hanseatic cities (read more here) of Königsberg, Elbing, Thorn, Danzig, Reval, Greifswald, Lübeck and Stralsund, as a kind of peace keeping force, while Albrecht and Erich started to round up the money needed for the ransom. Their efforts was however in vain, and in 1398 the cities’ representatives leave Stockholm, allowing Margareta to occupy the city. The conflict between king Albrecht and Margareta is definetely over.

Today the castle of Lindholmen is nothing more than a grassy mound, but in the 14th century it was one of the most important castles in the entire Danish realm

A free man

Albrecht returned to his Mecklenburg of old and ruled the land for years. In a letter dated 25th of November 1405, in the end, he was able to forgive the peoples of Sweden, Norway and Denmark for what evil they had bestowed upon him. The same date he also writes other letters, in which he states that he will no longer claim Swedish regions, but rather support his son, duke Erich. Albrecht dies 1412, and with him dies the Mecklenburg dynasty’s hopes for the Swedish throne.

Margareta, Bogislav and the Kalmar union

Margareta, her adoptive son Bogislav, the Swedish council and many other Swedish nobles were gathered in 1396 to the recess of Nyköping, which in short meant that the crown reclaims all estates and all land that has been given or claimed since 1363, when king Albrecht came to power. All strongholds an castles that was built during those years should be torn down if the queen so wished. But that wasn’t all that was discussed. The most important thing at the meeting was that the congregated potentates agreed that none of the three Nordic realms should wage war on oneanother. They had ”in all these kingdoms one lord and king”. The young Bogislav of Pomerania could look forward to a splendid position as king over a great realm.

He was crowned in 1397, and at the same time the Kalmar union was signed between the three kingdoms. The statutes of the union stipulated, among other things, that the descendants of the king should inherit the crown – a direct dichotomy to the Landslag, accepted in the middle of the 14th century. Also, each country should have right to their own laws, but at the same time they should henceforth be seen as one kingdom – under ine king. Margareta was still holding the reins until 1400 when Bogislav came of age and at least formally took over power from his mother. He reigned the new union between 1400-1439 with two interludes. He was however forced to change his name into the more proper Swedish name Erik – Bogislav was too strange a name for the Scandinavians.

1400 Erik came of age, and rode his Eriksgata the following year, but his mother was still holding most of the power; she was in no way willing to let go of her influence.

In 1402 Margareta negotiated with Henry IV of England to be able to marry Erik with Henry’s daughter Philippa. The negotiations went well, and Erik and Philippa was married in Lund 1406.

He, his young queen and his mother worked hard to strengthen the three kingdoms against first and foremost the Germans, in the form of the Hansa and the Teutonic order. Their measures included instating foreign vasalls to control Sweden, which eventually lead to unrest amongst the population.

Before that, however, they declared war in the Hansa, as they considered the trade confederation too powerful. On the side of the Hansa, the Holsteiners joined, and the Baltic region was thrown into a war that lasted until 1435, with some armistices.

Margareta died the 28th of October 1412, when negotiating for the city of Flensburg, which had been seized by the Holsteiners. She is buried in a magnificent sarcophagus in Roskilde cathedral in Denmark. Curiously enough, king Albrecht died the same year, the 31st of March or 1st of April. He was laid to rest alongside Richardis in the Doberaner Münster in Bad Doberan of the Mecklenburg area.

This article was written by Peter Ahlqvist.

This article is the final part of four. Read more in the same series here:

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 1 – The beginning

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 2 – The struggle of the lawmaker

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 3 – The age of the king

These pages might also prove useful:

Timeline of Swedish politics 1306-1412

Family tree of Swedish royals during the 14th century

Would you like to read more about Albrecht of Mecklenburg? Click here.

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 3 – The age of the king

Long live the king

The war against Magnus Eriksson had been an expensive one. Magnus had acted decisively when Albrecht went to Åbo to continue the siege after his marsk (marshal/military commander) Nils Turesson was killed in 1364. As mentioned, Magnus’ actions culminated in the battle of Gataskogen, where he was captured. At the opposing side were German knights, for example the mentioned Henrik van Ouwen, Rawen van Barnekow and Vicke van Vitzen. They expected compensation and rewards for their loyalty, but the Swedish coffers were appallingly empty and Albrecht had to find another way to pay off his countrymen. His solution was to grant the foreging knights land. During his first year as a king the young king was forced to pawn more than half of his kingdom. The Swedish nobles were outraged, which is easy to understand; if the king pawned land to Germans, there wasn’t much land left for them.

Furthermore, the Germans tended to see the Swedish commoners as little more than resources to be exploited. The Swedish model with a free, armed peasant class with extensive rights wasn’t at all what the Germans were used to, so they merely scoffed at the commoners’ claims. A chronicler described them as ”birds of prey” and it was generally agreed that the new masters ruled against tradition and law. In Sweden it was formally peace, as the old king Magnus had recognized Albrecht as king. This meant that nobody needed German and Danish mercenaries, which as a result became unemployed. In the following years the unemployed soldiers drifted through the lands, pillaging and stealing.

An old verse tells the tale of the relentless robbers

Jak wil idher tydha aff then rääff

som wäl weet badhe hool oc grääff

ther menar iak mz then legodräng

som haffuer fordarffuat badhe aker oc äng

the wilia alla til hoffua rijda

widh bondans kornladu at strijda

fik han eena kogerbysso oc pijla vti

tha skulle iw bonden til skogen fly

spangat bälte oc krusat haar

rostad swärd oc staalhandske widh hans laar

rijdher i gardh oc gar i stuffua

sidhan wil han fatiga bondan truffua

hustru huar är tin vnga höna

then skal tu ey länger for mik löna

ligger hon sik i bänk eller pall

bär henne fram oc äggen all

hon sitter ey sa högt a rang

iak slar henne nider mz min spiwtz stang

haffuer tu ey meer än ena gaas

then skulom wij i apton haffua til kraas

han beder uptända fempton lius

han drykker oc skrölar i fullan duus

thz monde the edela bönder söria

at legodrängar skola tolkin leek vpböriaI would like to tell you about the fox

That well know both hole and ditch

I mean by this the mercenary

Who has destroyed both field and meadow

They will all happily ride

By the farmer’s larder to fight

If he had a quivergun with arrows

The farmer would flee to the forests

Belt with metal plaques and curled hair

Rusty sword and a steel gauntlet by his thigh

He rides to the farms and goes in the house

Then he likes to force the poor peasant

Wife, where is your young hen

You should not hide it from me anymore

If she lies under bench or stool

Bring her to me along with her eggs

If she sits high on her perch

I will strike her down with my spear

Have you not more than a single goose

Tonight we’ll have it for a meal

He says to light fifteen candles

He drinks a shouts and feasts

That the noble peasants may mourn

That mercenaries should start such a game

This was, of course, a rebellion waiting to happen. But Albrecht was in no way out of the game. 1375 the old Danish king Valdemar Atterdag died, which meant that king Albrecht’s family could have a real shot at the Danish throne. Atterdag’s son Kristoffer was killed in 1363, which meant that the son of his oldest daughter Ingeborg was next in line. The good thing about this was that Ingeborg was married to duke Heinrich of Mecklenburg, king Albrecht’s older brother. Furthermore, Valdemar had signed a treaty with the Mecklenburgers in 1371, where he promised that the grandson in question should inherit the crown. Everything seemed to go Albrecht’s way – if his nephew, also an Albrecht, could be put on the throne of Denmark he would not only be rid of an enemy – he would also gain a powerful and rich ally.

There was only one problem. The treaty with the Mecklenburgers was never ratified by the Danish council. Instead the Danish nobles referred to an earlier, and ratified, agreement with the Hansa, where it was stated that the Hanseatic cities had a say when it came to which king that would rule Denmark if Valdemar should perish.

Enter Margareta

The Danish nobles turned to Margareta, the younger sister of Ingeborg. She had a son with Håkan of Norway, and because of Norwegian law he had already inherited the throne after his father. His name was Olof, and it was on him that the Danish highborns put their money. The conflict was a fact. The Mecklenburgers and the Holsteiners make an alliance to put young Albrecht on the Danish throne. They are lead by the old duke Albrecht of Mecklenburg – king Albrecht’s father, and invade Skåne in the end of the 1370’s. However, they achieve very little, and old Albrecht dies in the beginning of 1379. At this point king Albrecht of Sweden join the war to support young Albrecht (confused yet? It’s Albrecht VI von Mecklenburg who is in question here) in his struggle for the throne and to try and reclaim Halland and Skåne. He too achieves little, and in 1380 Danes and Norwegians burn the cities of Jönköping, Skara, Örebro and Västerås. In 1381, the war comes to a standstill and eventually it is discontinued. This, in effect, meant that the young Olof was elected king even in Denmark. As he was a minor, his mother ruled in his place, something that probably suited her quite well.

The mightiest man in Sweden

Albrecht may have been king, but in fact, he ruled very little of Sweden. Bo Jonsson Grip, the king’s drots (which meant he was the second in charge and also the supreme judge of Sweden) owned most parts of Sweden, including all of Finnland and the vast region of what was then called Hälsingland (now Norrland). More specifically, he owned or administered Stockholm, Nyköping, Kalmar, Viborg, Raseborg, Tavastehus, Korsholm, Öresten, Oppensten and Rumlaborg counties. But all good things must come to an end, and Bo Jonsson died in 1386. If king Albrecht could get his hands on even half of those estates, farms and castles, his fiscal problems would be over in a glimpse. He thought up a plan, and summoned the ten executors that were appointed to administer the deceased drots’ assets. None of them showed up, which was probably a wise move, but at the same time they took a stand by disobeying a direct order from the king.

But the king had another plan. He tried to force the widow of the drots, Margareta Dume, to choose him as her guardian. At the same time he wanted to reclaim lands and estates that the nobles ”unlawfully” claimed after the uprising in 1371. Last but not least he wanted to impose a special tax which would include otherwise tax-exempted lands. This was too much for the nobles, and as usual they tried to replace one master with another. They turned to Margareta and her young son Olof, king of Denmark and Norway. As Olof was a nephew of the late Magnus Eriksson (the ex-king who drowned), he was in fact entitled to compete for the Swedish throne. Ironically, it was just what the nobles feared in 1363, only now they saw it as their only chance to get rid of a hated garp (a medieval Swedish word for both a German and for someone who is a pain in the ass).

Allmighty mistress and proper master

Everything seemed to be set, and the Swedish nobility turned their hopes to the daughter of their old arch enemy, but the 3rd of Augusti 1387 Olof suddenly died from disease. It is easy to imagine that king Albrecht said his evening prayers with unusual enthusiasm when he heard the news. In theory, nothing could stop him now. Margareta was in an extremely precarious situation; her position, her power – her whole life – depended on her status as the queen mother of Olof. Now that he was dead she would quickly be swept aside. Only, she weren’t. A week after the death of her son she was elected protector of Denmark and ”allmighty mistress and proper master”. It is equally easy to imagine how king Albrecht just skipped his evening prayers when he heard those news. In february 1388 she was also elected sovereign of Norway. Her sister Ingeborg’s grandchild Bogislav of Pomerania, whom she adopted, was elected her successor.

In March 1388, one month after the election in Norway, she met the leaders of the opposition against the king at the Swedish castle Dalaborg, deep into territories that the king never really was able to master, at the western beach of lake Vänern. Most of them were part of the council; nine of the 12 members of the council were the above mentioned executors appointed by Bo Jonsson Grip. It is no exaggeration to state that those that congregated at Dalaborg were enemies of the king. They elected Margareta as allmighty mistress and proper master of Sweden, on behalf of the people and the realm.

This article was written by Peter Ahlqvist.

Read the fourth and final part here.

This article is the third part of four. Read more in the same series here:

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 1 – The beginning

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 2 – The struggle of the lawmaker

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 4 – Defeat and union

These pages might also prove useful:

Timeline of Swedish politics 1306-1412

Family tree of Swedish royals during the 14th century

Who was Albrecht of Mecklenburg?

Would you like to know more about Albrecht of Mecklenburg? Read more about his life here.

King Albrecht I of Sweden has already been presented by name in a number of articles, but until now we haven’t really had the opportunity to get to know him. The man that was to be Albrecht I of Sweden, was born around 1339 (the sources state everything between 1338 to 1340) as the second son of duke Albrecht II of Mecklenburg (1318-1379), and Eufemia Eriksdotter (1317-1370), sister of the Swedish Magnus Eriksson – a man that was to be contesting with Albrecht of the throne. In other words – these relationships made our Albrecht next in turn to the Swedish crown, after king Magnus Eriksson and his son Håkan. Albrecht’s father ruled the Mecklenburg area at the north coast of Germany between 1329 and 1379, and that was a task that would later pass on to our Albrecht after his elder brother Heinrich (III von Mecklenburg) had died in 1384.

Speaking of Heinrich – he married Ingeborg Valdemarsdotter, daughter of the Danish king Valdemar. Heinrich’s son, Albrecht IV of Mecklenburg, would later take part in the struggle for both the Danish and the Swedish thrones, as he was Valdemar’s grandson.

Apart from Heinrich, Albrecht had three siblings: Ingeborg, Magnus and Anna, but none of them played any significant role in Swedish politics.

When Albrecht got the opportunity to be the king of Sweden, he was in his early twenties. He came from a relatively small area in northern Germany, but what his country lacked in size it regained in diplomacy and ruthlessness. Still, it must have been hard stepping onto a throne in a country where everybody behaved differently and, for the most part, saw you as either a tyrant or a puppet – even with your experienced father backing you up. Albrecht went through a number of difficult situations, which he handled with various amount of success, before he retired to Mecklenburg to rule the area until his death.

Albrecht married Richardis von Schwerin, the daughter of Otto von Schwerin, the year 1359. A contract of marriage had been set up in Wismar seven years earlier. The couple had at least three children; the sources indicate another daughter, but this is not confirmed. The three children were Erik (1359/1365-1397), which was to be Albrecht’s successor for the throne of Sweden, Richardis Katarina (born 1370/1372-1400) and Johann.

Richardis died in 1377, and Albrecht married Agnes von Braunschweig, the daughter of Magnus von Braunschweig, the 12th-13th of February 1396. They had a son in 1397, known as Albrecht V. He didn’t get any children of his own, and died in 1423, only 26 years old.

Albrecht himself died the 31st of March or 1st of April 1412, the same year as his nemesis Margareta, and was laid to rest in the Doberaner Münster church, close to Rostock.