Ways of old

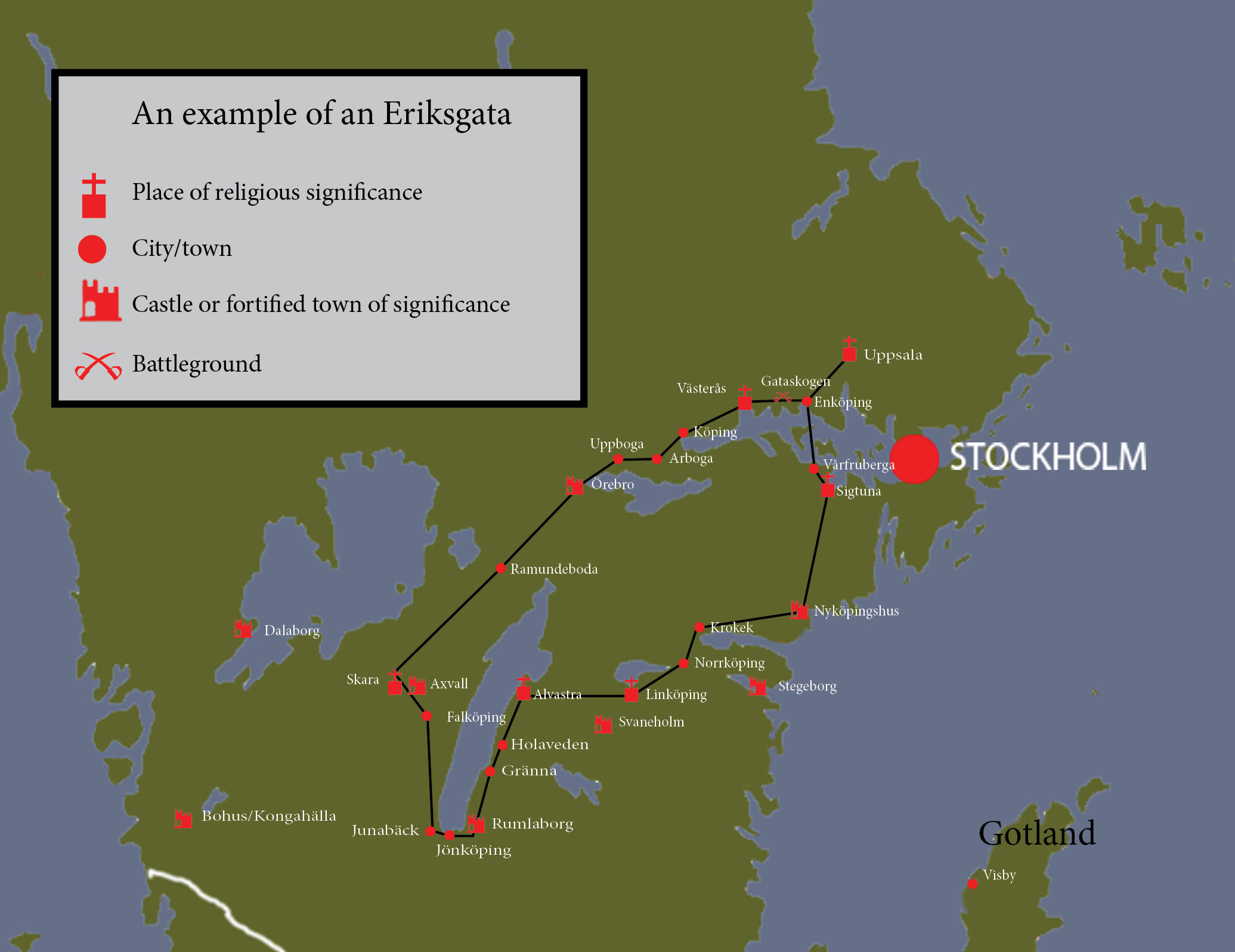

In many ways, Sweden was still a fledgling nation in the fourteenth century. There does not seem to be much national identity. Many probably thought of themselves as East Goths, West Goths, Svears or Finns. The king was elected in the area of Svealand, and then had to travel to the different areas to be accepted in the other areas. This journey was called Eriksgata (”Erik’s Way”) after the first king that made it. An Eriksgata was surrounded by rules and tradition. Failure by the king to follow them, was not taken lightly. The reign of Ragnvald ”Knaphuvud” (Short of head or Dumb head) was very short, as he ignored the rule of hostages upon entering Västergötland. This traditional rule means that the king needs to wait for ”hostages” or rather escort when entering a province. Ragnvald Knaphuvud was of the opinion that he was so powerful that he didn’t need any escort, and entered Västergötland with his own sworn men. The people of the area promptly killed him, and did not want anything to do with the kingdom of Sweden for several years after that incident.

In the latter part of the century a greater centralization of power starts to appear. The kingdom is becoming more structured and works more like a united nation than before. The power struggles between the king and the nobles dominates the national politics during the period. The true power was mostly concentrated to Sweden’s richest and most powerful man of all times; Bo Jonsson Grip. Only a squire (and hence not even a knight), he owned Finland (called ”the Eastern half of the Realm”) and most of two parts of the rest of Sweden at the time of his death in 1386.

A feud between brothers

Nu starb von dem hungere gar, der eyne herczoge Woldemar /…/ Do her des mochte getun nicht me, du starb her ouch yn hungirs we.

In 1319 the three year old Magnus Eriksson, son of the starved-to-death duke Erik, is elected king of Sweden and inherits at the same time the crown of Norway. Magnus was seen as the most fitting heir to the throne by his father’s supporters. A three-year-old on the throne suited the nobles just fine, since it in effect let them rule, even though the young king’s mother, the Duchess Ingeborg, was a bit more stubborn and powerful than the council of nobles really liked. She and her aide/lover Knut Porse planned an attack on the province of Skåne, which annoyed the nobles. In general, they also disliked the influence Knut Porse had over Ingeborg, and they had no intention whatsoever of helping them out. However, the expedition to Skåne couldn’t be successful without support from somebody, and that somebody turned out to be the north German nobleman Henrik of Mecklenburg. By betrothing her four year old daughter Eufemia to Henrik’s son Albrecht the elder of Mecklenburg, Ingeborg had the support of the north Germans. The campaign against Skåne was a failure, but the bond between the Swedish royals and the Germans remained, something that would be of the greatest importance some years later, as we will well see.

Enough is enough

The council lost what patience they had with Ingeborg. Fighting a long war on Novgorod in the Finnish part of Sweden, they certainly didn’t need another front. In 1323 the decided that something had to be done. They signed a treaty with the Novgorodians at the castle of Nöteborg, and thereby regulated the Swedish/Russian borders in Finland. Then they turned on the capable duchess, and besieged her strong castle of Axvalla. 1326 the nobles and Ingeborg finally come to terms and she is forced to give up much of her power. She is given the small Dovå castle to support herself.

Something rotten in the state of Denmark

At the same time, king Kristoffer of Denmark was in quite a pickle; his predecessors and himself had been leading an irresponsible foreign policy and hence they had to pawn one Danish region after another to creditors from Holstein in northern Germany. Skåne and the better part of mainland Denmark was under German rule. A lot of the people of Denmark and Skåne was less than satisfied with the ruling Holsteiners, because they were ”merciless” to the commoners. Under the command of the archbishop of Lund, Karl Erikssøn, the people rebelled against count Johan of Holstein, besieged Helsingborg and seized the count’s other estates in 1332.

The year before, in 1331, the young Magnus Eriksson, the son of countess Ingeborg, came of age. He was 15 years old and hence acceeded the formal royal power from his mother. He immediately proceeded to confirm the old privilegies of the rebelling archbishop Karl – even though he in theory was was subordinated to Johan of Holstein, who owned Skåne and therefore was the only person that really could confirm any privilegies of old. The young king took a longshot to consolidate his power in the wealthy province.

Magnus gain Skåne – and lose it

The counts of Holstein wanted to end the rebellion and mustered an army at Sjælland to come to Helsingborg’s rescue. Magnus, in his turn, sent ships and soldiers to oppose the counts, but he was in the end convinced to refrain from violence. He was allowed to buy the province of Skåne for the immense sum of 34 000 marks of silver (about 8 000 kilos of pure silver). The people of Skåne, including the archbishop, the nobles and number of burghers and peasants voluntarily swore an oath of fealthy to Magnus, whom they looked upon as their master and king. He was crowned in 1336. After this Magnus begins calling himself ”the king of Sweden, Norway and Scania”. Also, this is about the time when three crowns start to appear as a symbol of the realm.

Skåne held one of Europe’s most important markets which generated an enormous tax revenue, a prequisite for Magnus ability to repay his huge loan. But Skåne slipped out of hus grasp sooner than he could ever anticipate. Valdemar Kristofferssøn, more known as Valdemar Atterdag was celebrated as Danish king in 1340. He had come to terms with the Holstein counts after great efforts, cunning diplomacy and military action. In 1348 Denmark was his. Even though he in 1341 had agreed on an ”unbreakable peace” with Magnus, and 1343 renounced his claims for Skåne, he conquered the province after only a couple of months on campaign. The Swedish army under Erengisle Jarl and Karl Ulfsson is camped at lake Ringsjön but stays passive. The only thing they seem to manage is to kill the exiled Bengt Algotsson (we will return to Bengt Algotsson later); it is said his murderers were Karl Ulfsson of Tofta and Magnus Niklisson. Then the Swedish army returns north. The nobles showed very little interest in fighting in Scania. The revenues from the market in Skåne was no more, and king Magnus could never be free of his debts – he only switched creditors.

Being on a roll, Valdemar sets sail for the islands of Gotland and Öland in 1361. Öland is taken relatively easy, and despite warnings from Magnus, the Gotlanders are taken by surprise. The campaign culminates the 27th of July in the battle of Visby where almost 2000 Gotlandish commoners were slaughtered by Danish and German mercenaries, and thrown into massgraves. Visby is plundered, and according to legend, Valdemar forces the inhabitants of the city to tear down a part of its city walls. Even though the attack was a great success, it was a mistake; Visby was part of the Hanseatic League. The city of Lübeck starts negotiations with the Swedes in August, and a combined attack is planned. The Swedish nobles, however, are showing usual reluctance to support their king. The mustering of troops is going slow, but about a year after the attack on Visby, Magnus (with some help from his son Håkon) has gathered enough men to launch an attack on Valdemar in the city of Helsingborg. 27 koggs and 25 other vessels set out to teach the Danes a lesson.

This article, written by Johan Käll and Peter Ahlqvist, was in part previously posted on our old webpage under the name 14thc Political climate.