Skåne is lost

The Hanseatic/Swedish attack on Valdemar and Helsingborg is a fiasco. The joint effort is disorganized and lacking in communication. The Hanseatic fleet lose 12 cogs (for which Johan Wittenborg, the mayor of Lübeck and also the commander of the fleet, is executed on his return to Lübeck). Evenso, the battle is a huge loss also for king Valdemar; his son, prince Kristoffer, is hit by a stone (probably from some kind of siege engine – the sources doesn’t mention any kind of firearms. Even so, a 16th century source states that he was shot by some kind of gun) and dies a year after the attack. Soon after the battle, the Hanseatic league and Valdemar agree to a truce – against the will of king Magnus. Skåne was irrevokably lost.

Duke Kristoffer, son of Valdemar Atterdag. He was mortally wounded at the battle of Helsingborg 1362, but didn’t die until 1363

A troublesome king

But the troubles began even before Magnus lost Skåne. Let’s look at the time before Magnus lost the wealthy province. When Magnus came of age he didn’t seem to share the Swedish nobles’ point of view of what is good for the country. He started to restrict the power of the nobles, and tried to make Sweden a country where the crown is passed down from father to son, as in Norway, where he also is king. Not surprisingly, this was bad news for the nobles – they wanted to put a weak king of their choice on the throne, not the son of an independent, mighty ruler. In the so called Magnus Eriksson’s Landslag (”The Magnus Eriksson law of the land”) of 1349 it is therefore stated:

Nu ær til kunungx rikit i Suerike kununger væliande ok ey ærvande

Now is to the kingdom of Sweden king elected and not inherited

Furthermore, it states that a man that is to be elected king is someone:

Huilkin en af inrikis føddum – ok hælzt af kununge sunum

Who is born in the kingdom and preferably son of a king.

Landslagen was composed by a council of lawmen, headed by the father of Birgitta Birgersdotter (internationally known as saint Bridget/saint Birgitta), and based on earlier county laws. This is the first law to pertain to the country as a whole, hence its name, and therefore an important milestone in the forging of a state. Even though Landslagen bears his name, Magnus never officially sanctioned it, quite possibly because he did not agree on above cited paragraphs…

Noble malcontent and a jealous son

King Magnus had two sons with his queen, Blanka of Namur. They were called Erik and Håkan and their father managed to get them both elected as king. Håkan, the younger, was to become king of Norway when he was old enough. He acceeded the Norwegian throne in 1355. Erik was to succeed his father at the throne of Sweden, and as his father was still decently young, it looked like a long wait for Erik. At this time the young nobleman Bengt Algotsson enters the arena. He is hardly mentioned in the sources before the king’s second crusade against the russians in 1350, but only five years later he had become dubbed a knight, gained a seat in the king’s council and was appointed duke of both Finnland and Halland. No doubt he was important to the king, but noone knows exactly why. Rumours of a homosexual relationship between the king and Bengt circulated. The gossip worsened after the Black Death hit Sweden in 1349-1350; Birgitta Birgersdotter, which had become very powerful due to her status as soon-to-be-saint, declared that the plague was caused by the wearing of immoral clothing and, worse, the king’s scandalous relation to another man. She dubs him Kung Smek (”King Fondle”), a derogative that sadly has survived through the ages and stuck to this otherwise quite able king. It is hard to tell if there is any truth in the claims, but frankly, it is not really important.

Erik rushed into action. He knew that many of the nobles hated Algotsson and his sudden rise to power. Most of them were also outraged by the king’s will to restrict the power of both the clergy and the nobles. It was very clear that Magnus wasn’t as weak as they had hoped, and now he was a direct threat to their way of life. Another part of the parcel concerned Magnus’ debts. Some of the nobles stood as guarantee and had to pay his creditors. On top of it all, Magnus faced excommunication for his disability to pay his debts to the pope. He and a band of nobles, as well as five of Sweden’s seven bishops, declare war on Bengt Algotsson in october 1356. This is in part a covert war on Magnus, who doesn’t take any particular action against his son. In 1357 a treaty is signed. Magnus agrees on giving his son great parts of the kingdom to his son. Erik takes on the title of king of Sweden, and banishes Bengt Algotsson from his new kingdom. Bengt Algotsson flees to Scania, where he is killed some years later (mentioned in this article). The new king of Sweden rules the country along with his father for two years, and constantly takes the liberty of ignoring the statutes of the treaty from 1357. His reign, though, doesn’t last very long. He dies in 1359 and Magnus becomes sole king again.

Even more trouble

In 1363 Magnus’ remaining son, Håkan, king of Norway, is forced to honor an agreement with his father’s nemesis king Valdemar. Before the troubles began, he was betrothed to Valdemar’s daughter Margareta. When her father waged war on Sweden, Håkan broke the agreement and made a new one: he betrothed Elisabet of Holstein, sister of count Henrik of Holstein, in 1361. In late winter 1362 she was sailing to Sweden with her escort to marry Håkan, but a storm drove the ship to Bornholm, which was controlled by the archbishop of Lund – loyal to king Valdemar. The archbishop declared that no marriage could take place between Håkan and Elisabet, as this was against canonic law; from the archbishop’s point of view Håkan was still to marry Margareta. They tied the knot in 1363.

Hammershus at the island of Bornholm, south of Skåne. This must have been a formidable fortress in its day

The Swedish nobles seethed with fury. Their arch enemy Valdemar was now bound to Sweden, which could well mean that a son born by his daughter could be king of Sweden – and run his grandfather’s errands. Meanwhile, the counts of Holstein were disappointed as their possibility of an important alliance was made impossible. The Hanseatic league worried about which consequences this new alliance could have when it came to their influence in Sweden and at the market of Skanör and Falsterbo.

Even more noble malcontent

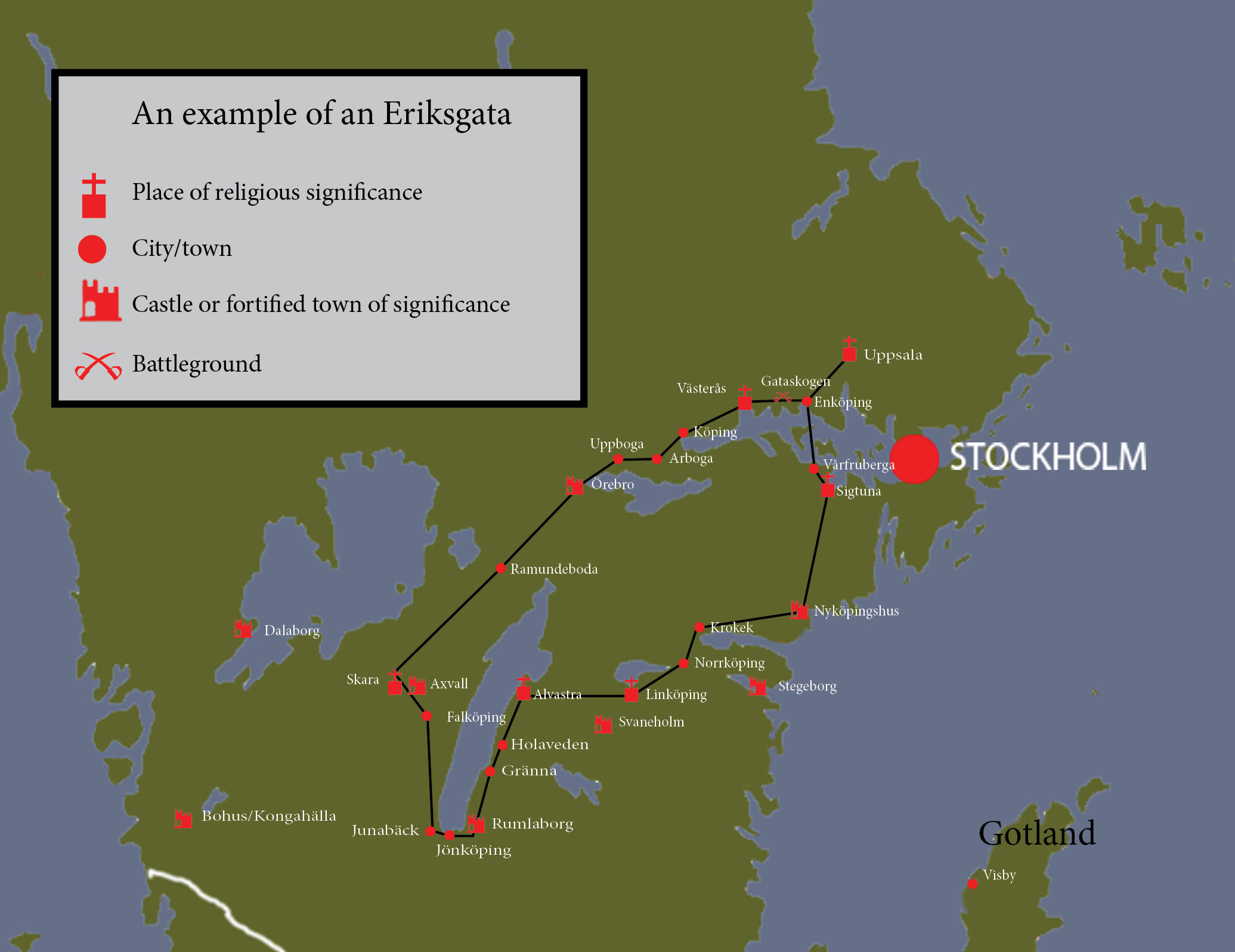

The Swedish nobles acted first. Some of them, including the powerful Bo Jonsson Grip, went to Mecklenburg to offer duke Albrecht the crown of Sweden. His son, Albrecht the younger, was appointed the task. But what about that Landslag, which stated that a Swedish king must be born in Sweden? No problem. In this article you will learn the background of why Albrecht was actually related to king Magnus. In fact, he was his nephew, as Magnus’ sister Eufemia was married to Albrecht the elder. This was part of the politics of Magnus’ and Eufemia’s mother duchess Ingeborg before her campaign against Skåne in 1322.

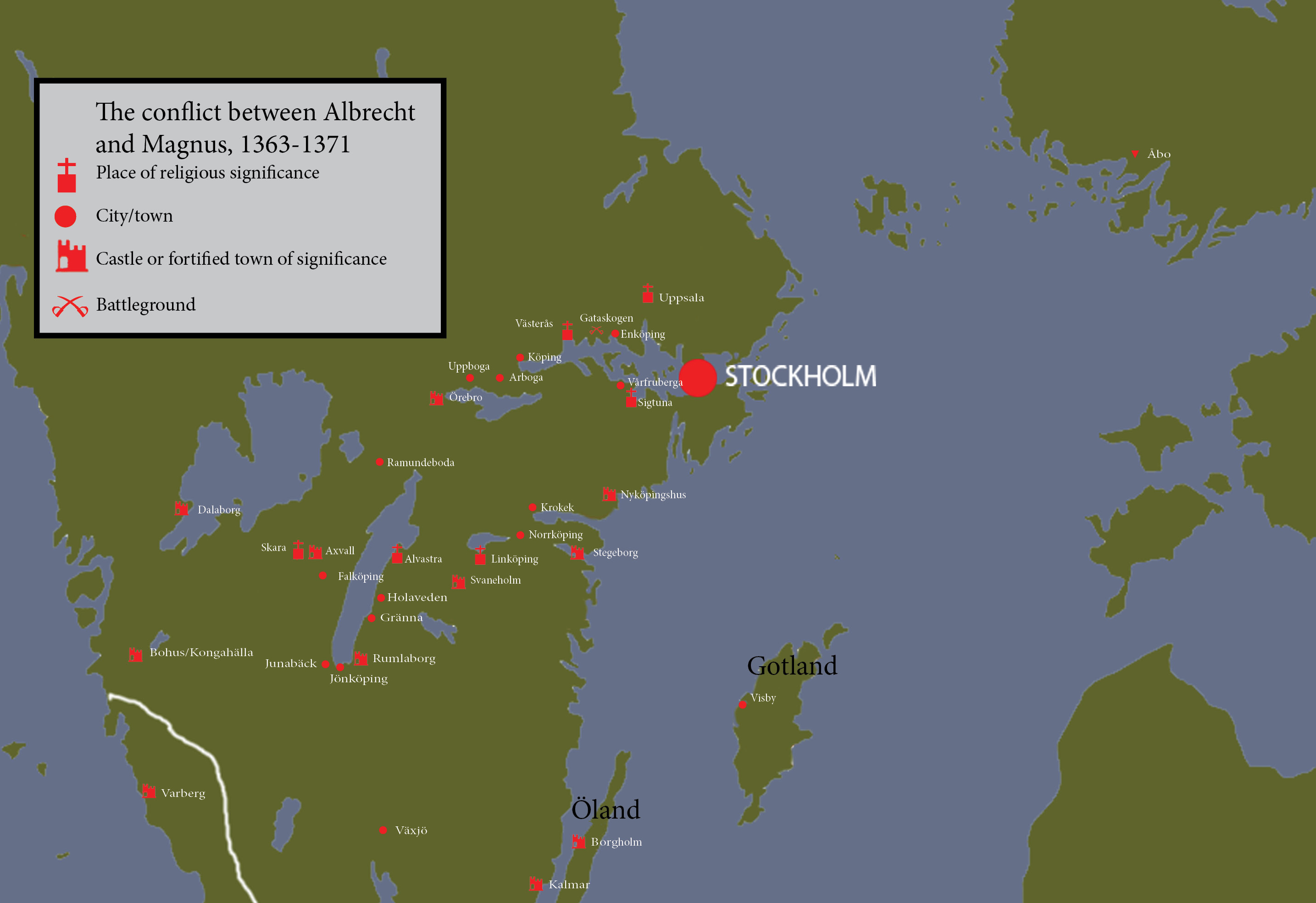

Enter the Germans

Many of the burghers in the Swedish cities were actually Germans, which meant that the cities joined the two Albrechts when they and the Swedish nobles arrived in Stockholm with a fleet and about 1 500 soldiers the 29th of November 1363. The same day the burghers of Stockholm swear allegiance to Albrecht the younger and promise to ”live and die” with him. This marks the beginning of a time of strife; Magnus and his son Håkan of course had one or two things to say about the new ”king”, and mustered troops to face the invaders. In february 1364 Albrecht the younger was really elected king, and by july Håkan and Magnus are forced to negitiations after losing the castle at Örebro and the newly erected Svaneholm. A truce is signed by both parts but in the autumn the hostilities continues, and Albrecht himself lead the siege of Åbo castle in Finnland.

The 3rd of March 1365 Magnus and Håkan march from Arboga to Västerås, determined to capture Stockholm. Just before they reach Enköping they encounter an army of Albrecht loyalists at Gataskog under the command of Henrik van Ouwen. Father and son suffer a bitter defeat. Håkan is badly wounded but manage to flee the battlefield, while Magnus is captured and taken to Stockholm. The remaining forces of Håkan and Magnus withdraw to Västerås and Arboga. During the summer they negotiate for terms with king Albrecht’s vassal Raven van Barnekow, bailiff of Nyköpingshus. After this victory, most of the Swedish nobles join Albrecht’s side.

Håkan continues the fight

In 1366 Håkan has recovered from his wounds and feel fit enough to reengage king Albrecht. He summons his troops and attack Öland, where the stronghold Borgholm is taken. Soon after, the duke of Sachsen, Erik – one of Valdemar Atterdag’s men occupy the northern parts of the province Halland, and meanwhile king Valdemar himself lays siege to Kalmar to help his son-in-law. This of course puts king Albrecht in an even tighter spot; now he is fighting a war on two fronts. His father, Albrecht the elder, is a sly old politician however, and starts dealing with Valdemar directly. He promises Valdemar big chunks of Sweden, and the Danish king withdraws his troops. This however, is nothing but a ruse; old Albrecht knows that the Swedish council won’t ever agree to such terms, and he is right. They refuse, but the old tactician has bought his son a great opportunity to finish the fight with Håkan before he has to attend to the Danish problem.

Old Albrecht’s plan is successful. The war starts going badly for Håkan. Some time in 1367, Albrecht’s troops manage to re-capture Borgholm and in 1368 Albrecht joins a federation of Hanseatic cities, which in the beginning of the year occupied Köpenhamn/Copenhagen, Skåne and Gotland, and at the same time managed to pillage the Norwegian coasts, which forces Håkan and Norway into a truce. In 1369 The war against Denmark ends, and both the Hanseatic league and king Albrecht withdraws after forcing Valdemar Atterdag to accept their terms.

However. Already in 1370 the Swedes are growing weary of their new masters the Germans. King Albrecht is now without the support of the Hansa, and Håkan seizes the moment. In the beginning of 1371 an uprising against king Albrecht starts in the province of Svealand. Commoners urged their likes in other parts of the realm to rise against the Germans, and wanted the council to lead the uprising. They hade grown weary of

wold och orätt, träldom och omilde som I och wij och aller Suerikes almoge tolt haffuom aff tyskom mannom

violence and unjustice, serfdom and unkindness that we and you and all Swedish commoners have endured from German men

They wanted to rid Sweden of

herra Albrect som wor konunger skulle wara, huilkin som är en retter meenedhare och hans fadher, rikesens i Swerige rätta förrådhare

lord Albrecht who should be our king, but is a real liar and his father, a true traitor to the kingdom of Sweden

Actually, they declared that they didn’t feel any loyalty to the king or any German at all. Instead, they wanted to live

vnder then erliga och godha herran konung Magnus, ey tess sidher at han fongen är, huilken wij vthaff then wånda hielpa wiliom med allo wåro macht, och hopp till Gudh haffua vnder honom, at wij med honom vnder rett och lagh bliffua skolom, och med allom them som med oss bliffua wilia, wiliom wij gladheliga liffua och döö, och the oss emoot stonda och oss ey hielpa wilia, them wiliom wij nidhra och förderffua och lijka holda widher the tydzska

under the honest and good lord king Magnus, even though he is a captive, who we out of pity want to help with all our power, and hope to God under him, that we will obey justice and law under him, and all who is with us we will gladly live and die alongside, and those against us and those who would not help us, we want to bring down and destroy and treat as a German

Some knights and squires seems to have joined the rebel army, but mostly it consisted of burghers and peasants. The king was abroad at the time and had no time to muster his troops. The rebels lay siege to Stockholm and Bo Jonsson Grip, king Albrecht’s second in command, was forced to negotiate. Magnus is freed from captivity and is granted the provinces of Västergötland, Värmland and Dalsland to be able to provide for himself, although he is obliged to recognize Albrecht as king and to pay the huge sum of 12 000 mark to Albrecht. Albrechts himself is forced to sign a document that in practice makes him powerless. Lands and titles he had given to his supporters were withdrawn and the king himself had to deed his personal domains to the state. He also have to admit that his knights and servants have been a bit too rough on the Swedes, but claims this was going on behind his back, and that the people responsible for the heinous deeds is being harshly punished.

The Swedish nobles were happy. They were now able to claim land for themselves, which made the balance of power completely different. The real power now lay with Bo Jonsson Grip – the greatest landowner of all times in Sweden.

A new era

But at the Swedish throne, there was a German. The nobles imagined that they would be able to control a 26-year old newbie of a king better than they could an old experienced one like Magnus. But their hopes crumbled fast enough; Albrecht was no puppet, and he had a completely different view on how to rule than the Swedish nobles, indeed most Swedes, had. He didn’t recognize the peasants as a free class; he looked upon them as serfs, just like in his old country. Albrecht ruled with his experienced and ruthless father as support. Both his father and his grandfather were known to break oaths and to excercise a very practical type of politics. Once again, malcontent started to brew.

At this time, the old ex king Magnus resided with his son in Norway. During a boat trip across Bømmelfjorden in the end of 1374 he drowned, and until this day it is not certain where he rests.

An image from the Mecklenburgischer Reimchronik, 1379. It shows Albrecht the older handing his son the royal banner of Sweden. The three crowns are still used as a symbol in moden day Sweden

This article, written by Johan Käll and Peter Ahlqvist, was in part previously posted on our old webpage under the name 14thc Political climate

What happened next? Read more in the next article.