I came across this free, downloadable publication on how to build traditional clay ovens – it will come in handy when we finally decide to build one for the company! Plus, there are loads of other resources on the web, such as these: The Bread Oven: Symbol of Colonial Liberty/A Large Clay Oven, Building and Using a Medieval-Style Hemispherical Bake Oven and The clay oven – how to build a clay oven in eight steps. The page even includes pizza recipes!

Etikettarkiv: 14th century

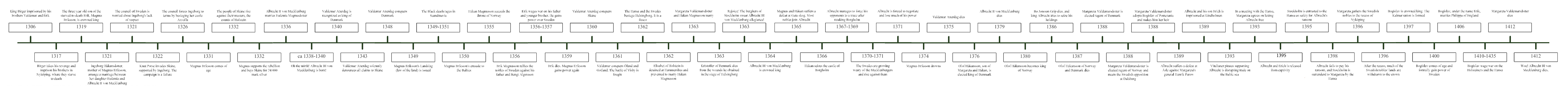

Timeline of Swedish politics 1306-1412

History during the 14th century can be quite confusing, and it’s more or less impossible to write a chronology in common prose. That is why we have made this timeline. Hopefully it will help you out when trying to understand the different schemes, alliances and events that took place during the period.

Click the tiny image to make it (a lot) bigger.

Read the 14th century history of Sweden in more detail in these pages:

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 1 – The beginning

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 2 – The struggle of the lawmaker

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 3 – The age of the king

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 4 – Defeat and union

This page may also be helpful:

Family tree of Swedish royals during the 14th century

Coping with winter

Wintertime was a time of travel in Sweden. The frozen riverbeds and bogs supplied virtual highways for sleighs and skiers. Summertime you where mostly restricted to climb the highest ”hole roads” (swe: Hålvägar), suitable only for sumpter horses. Much campaigning was done wintertime because of the ease of transportation. Also, the peasants were not needed to tend crops as much during winter. One drawback would be the lack of daylight, but at full moon and a clear sky the winter night is not very dark. Coping with cold is not as hard either. Firstly the Swedes of that time where used to be outdoors most of the time. Secondly, cold is mainly a factor when you stand still. Down to -15 to -20 degrees Celsius you will do good with just two woollen tunics as long as you are working or are in motion. As soon as you stand still you will need warmer clothes though, as your body will not generate warmth through being active.

Most things concerning winter campaigning is not about to clothes however, but of how you conduct yourself. Don’t stand in snow for long times. Stand on isolating pine branches. Don’t wear warm clothes on the move and get sweaty, put them on during breaks. Drink and eat regularly so the body have energy to keep itself warm you. Change wet socks right away, as getting wet is the best way to freeze. All these things were known even to medieval man as being outdoors was everyday life for them. They where probably more weather resistant and rugged then us normal modern weaklings and may have put up with a bit more discomfort then we are willing to endure. In Albrechts Bössor we are active the year round. Each year we stage a small one day winter march to test our gear to see that it will cope with winter conditions. This would have been vital for Swedish soldiers since, as stated above, many wars where fought wintertime. Thus we have found out some things that will be different from normal campaigning. So, there are some things one can get to make life in the wintertime easier.

Water

Although snow is water of a sort it is not always suitable for drinking. First of all, it cools you, and secondly its dry and don’t quench the thirst as good. For cooking, snow is excellent though, so there is no lack of water when in camp where there is snow. One problem that we encountered was that the water in the leather canteens froze. This resulted in that some of the canteens, that used a cork, was frozen shut and could not be opened at all. The one using a wooden plug could be pried open and the layer of ice that had formed inside hacked through with a dagger to get some drinking water. We recommend that canteens should be carried inside your clothes and let the body heat warm them, as is usual in modern days.

Winterclothing

Mittens and gloves

Mittens are a vital part of the winter gear. Hands get cold easily as the body draws heat from the extremities first to preserve it for vital organs. Five finger gloves where used as well as mittens and three fingered mittens. They could be in ordinary wool, felted wool, naalbinded, felted naalbinding or leather. No fur lined gloves have survived but it is very likely they have been around.

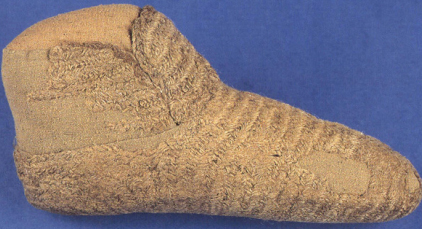

Socks

The feet are most often prone to getting cold while walking in snow so socks is rather essential. Maybe the medieval hikers made use of straw, stuffing it into oversized shoes, to keep warm. This is known to have been practised later on. However we have no evidence that they did so during the 14:th century. Naalbound socks however seems to have been in use.

Cloaks and coats

The cloak was used in Scandinavia in the 14th century maybe more then down on the continent. Coats also see good use, if we can judge from surviving documents from the time. The scholar Eva Andersson say coats and cloaks have been worn by both sexes even if cloaks seem to have been worn more by women than by men. Men seem to have preferred coats. Winter coats would have been lined for warmth, either with a thicker wool or with fur. Maybe furs have been worn as they where, that is, with the fur out. It is hard to tell from manuscripts as they do not use the terms the same way we do now. Pictures showing men wearing furs is picturing heathens in most cases and it is therefore not easy to use as reference on how ordinary people would dress. It seems to have been most common to wear the collar of the hood under the cloak/coat.

Hats

Although most hats used summertime will have been in use even wintertime the hood seems to be very popular during cold and harsh weather. It is also an almost perfect piece of clothing for this and its popularity is understood by all that has owned one. A lined hood, either with woollen cloth or with fur, will keep you warm and snug in winter. Anyone having had a lump of snow dumped inside the collar of your jacket when stirring a tree, will also know to appreciate the hood and its protecting collar. It also serves well to keep the neck warm as scarves don’t seem to be in use. As stated above it seems to have been practice to wear the collar of the hood under the cloak or coat, but over the tunic. This will save you from getting the collar blown up in your face when the wind comes. Other hats can include fur lined hats or just simple woollen ones. Fur lined hats are mentioned in contemporary documents and would have been worn even in summer. Hats with fur on the outside do not seem to have been popular though. On a pillar in the Linköping dome one can see hats on soldiers that are probably naalbound. Naalbound hats might have been more common than we know of now.

Shoes

Winter shoes differ from summer shoes mainly in that they need to be a bit bigger so that you can fit some kind of extra warming material in them, that is socks or such. An extra thick sole is also preferable to isolate from the ground. A shoe with a thick sole of cork has been found in Stockholm and is dated to around 14th century, as well as a sole with traces och naalbinding on it. Pattens is also of use in that matter. Maybe extra inner soles have been in use, but we know little of that. Traditional soles of birch bark was used in Sweden in old days, but if this habit dates back to 14th century we don’t know. They are excellent in keeping the feet warm though. Winter shoes should also have a bit of shaft on them to keep the snow out.

The winterdress reconstructed

These are some examples of the winter dress reconstructed and tested in outdoor activity wintertime. In general, they work as good, if not better then modern clothes.

Gloves

Gloves are vital since the hands get cold fast. Here are two pairs of naalbound gloves, three fingered and thumbed model, and one pair of three finger gloves made of hard felted wool lined with sheep fleece. The fleece lined gloves almost proved to warm. The felt, felted with earth, is very weather resistant.

The dress – Travel

On march, lighter clothing is worn since activity will keep you warm, especially if you carry a burden. The dress below shows a man on march. He wears a tunic (Swe: Kyrtil) and a super tunic (Swe: överkjortel) or Cote and Surcote. The air trapped between them will keep his body heat. Therefore they should not be to tight. He also sports a hood lined with fur. This one with black fur, being in fashion in late 14:th century. This hood was indeed very cosy in the chill winds. Also, he have double hose. These can be seen on illustrations where you see one pair rolled down. As always in winter clothing, the key here is layers. A pair of naalbound mittens and socks tops him of and makes him ready to travel the woods of King Albrecht’s Sweden.

The dress – reinforced

For taking breaks and standing still this dress in reinforced with a coat. The coat is made of rough felt, felted with earth to make it very weather resistant and water resistant. It is also lined with hare fur. This coat is very warm and will keep out water and wind like a charm. Combined with the hood it is an excellent winter garment.

A coat can also be lined with a thicker wool. Like this coat with a felt outside and a lining of a more ”airy” wool inside. The ”paired” buttons seems to have been more common on these kind of outer garments then on regular cotes.

The cloak

Although a bit out of fashion the cloak was used during the later 14th century, especially by women. Men carried them as well of course and they are rather good at keeping you warm. The drawback is that it is hard to work in them. As soon as you move too much, the warm air you have collected inside it escapes. Although, we used a cloak to test it. It is made from heavy wool and lined with a nice red and black striped wool. It is a rather heavy piece of clothing buttoned by three buttons. It is better to sleep in it than to work in it.

This article, written by Johan Käll, was previously published on our old webpage.

Mått och vikter under 1300-tal

Denna artikel bygger helt på, och är i många fall tagen rakt av ifrån boken ’Vad kostade det’ av Lars O Lagerqvist och Ernst Nathorst-Böös. En kul bok med prisuppgifter från 1170 till 1995, men även med många bra översikter om gamla mått, vikter och valutor. Jag har tagit bort information om vikter efter medeltid där så förekommer.

Aln – Svealand, Östergötland, Gotland 56cm. Västergötland 64 cm. Öland 52 cm.

Ankare – 39,25 liter.

Bok – 24 ark skrivpapper. 20 bok = 1 ris.

Centner – 100 skålpund = 42,5 kg. Som Bergvikt 8 lispund (60 kg).

Decker (däcker) 10 st (mått för skinn och hudar).

Dussin – 12 st.

Famn – 1,78 m. Som vedmått varierande, mellan 3 och 5.65 m

Fat – 157 liter (flytande) 170 kilo (om Osmundsjärn, dvs järnet i ”råvara”) 1/32 tunna (spannmål).

Fjärding – Våta och insaltade varor, 12 kannor = 32,4 liter. Torra varor, 4 kappar = 18,3 liter.

Fot – 0,2969 meter = 1/2 aln, kan variera.

Gross – 12 dussin = 144 st.

Jungfru – 1/4 kvarter = 8,2 cl.

Kanna – 2,7 liter.

Kast – 4 st. 20 kast = 1 val (om fisk mest).

Kubikfot – 10 kannor = 26,17 liter.

Lass – skattepliktig körning av varor som varierade. Vanligen 2-3 skeppund. För hö mycket varierande.

Lispund – 8,5 kilo.

Lod – 13,16 kilo.

Läst – 12-13 tunnor. Ibland ifråga om vägda varor 12 skeppund.

Mark – 205-210g. Om järn och koppar 340-375 g. Markpund – Lispund om 6,8 kg.

Mil – 10, 689 km. Smålänsk mil 7,5 km. Västergötland 13 km. Dalarna och finland 5-6 km.

Ort – 4,25g. Som rymdmått samma som ’jungfru’.

Oxhuvud – Rymdmått – 90 kannor = 236 liter. Kan vid import av rödvin vara 225 liter.

Pund – Samma som lispund.

Skeppund – Oftast 170 kg. För järn och koppar användes 5 olika viktsystem mellan 136 och 194,5 kilo. 1 skeppund = 20 lispund.

Skålpund – 0,425 gram = 32 lod.

Skäppa – 24,8 liter.

Spann – Mycket varierande, Stockholm 47 liter, södra Norrland 30-60 liter, Götaland över 50 liter.

Stavrum – Mått för ved, varierande, ofta 6m

Stig – Kolmått, ca: 20 hl, Dalarna 17.-18 hl.

Stop -1/2 kanna = 4 kvarter = 1,3 liter.

Stycke (tyg) – 30 m (lärft/ylle) 15 meter (bomull/siden).

Timmer – 40 st. Om skinn.

Tjog – 20 st.

Tum – 2,47 cm.

Tunna – Varierar efter användning. Fisk och Öl – 125,6 liter. Smör – 16 pund. Spannmål – 142-165 liter.

Val – 20 kast á 4 st (om sill med mera).

Åm -144 liter (vin), kan dock vara 157 liter.

Den här artikeln, som är skriven av Johan Käll, fanns tidigare publicerad på vår gamla hemsida.

Handgonnes and cannons of the middle ages

We could start this text by telling you about the Chinese origin of black powder, as can be found on dozens of pages on the web. But we won’t, because it’s not relevant. This article is about the use of handgonnes and black powder during the European middle ages, and that is a whole other thing. So we’ll start at black powder as a phenomenon.

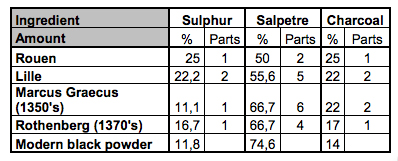

Gunpowder

In medieval Sweden gunpowder was called just ”pulver”, wich translates into ”powder”. There are quite a few old powder recipes still around, and the ones that suits our selected historical period

are referred to as, for example, Rouen, Lille, Rothenburg and Marcus Graecus. They all use the same ingredients, but the amounts differ. In the table below, they are compared to a modern ”perfect”

gunpowder.

Tests made at the Middelaldercenter in Nyköbing, Denmark show a correlation between higher muzzle velocity and higher amount of salpetre. The ingredients were ground up and mixed, resulting in a so called dry mixed powder. This can be used as it is, but it will be more effective if mixed with alcohol, shaped into bars or pellets and then ground again, producing wet mixed powder or meal powder. The alcohol dissolves the salpetre, and lets the tiny sulphur crystals divide and evenly on the grains of charcoal, making the powder burn more even. It is important to note that there has

been some debate about the use of alcohol in medieval gunpowder, as distilled beverages is barely known at the time. However, sources speak of a ”Henricus Brännewattnmakare” (Henricus, maker of burnt (distilled) water, meaning a producer of alcohol) in the city of Lund in the 1350’s, wich means that alcohol was in use at the time. If it was used to make gunpowder we do not know. Sulphur could be collected in volcanic areas in Iceland or Italy, while salpetre was produced by collecting dung and urine from livestock, and processing it, to extract the salpetre. Charcoal was abundant in medieval society.

Bössa?

The name of our group contains the word ”Bössor”, and in modern Swedish ”Bössor” means some sort of handgun like a rifle or shotgun. In the middle ages the term ”bössa” (sg.)/”bössor” (pl.) is applied to both handgonnes and cannons. In other words there are two different types of ”Bössor” in the fourteenth century, and it can be used as a very rough measurement regarding calibre and purpose; ”Stenbössa” – firing stones, and ”Lodbössa” – firing lead shot. The ”Stenbössa” seems to stand for larger calibre – possibly a cannon, whilst the ”Lodbössa” seems to have had smaller calibre – possibly a handgonne.

The projectile

The handgonne and the medieval cannon fired mainly lead shot (”lod”), stone balls, ”grape shot” or arrows. The use of arrows is a bit peculiar – it doesn’t seem to have any obvious advantages in comparison to stone balls. One theory is that the cannon presented an alternative to the so called ballista (a siege engine for firing huge arrows), and that gunpowder was just another method of propelling the projectile. The lead shot was probably cast by the gunner himself, using a cast made of sand stone, soap stone or bronze – as there was no fixed system for calibre, each man had to provide for himself.

The grape shot (Swe: kartesch) , which turned the handgonne or cannon into sort of a shotgun, was used against people and animals (like war horses) at close range. Virtually anything could be used as grapeshot, but shards of flint seem to have been common, as the razor sharp flint shards inflicted massive damage. The grape shot could be free loaded, or put into a triangular container for bigger guns; the Museum of Medieval Stockholm displays some of these, found on a sunken ship. When fired, the walls of the ”pyramid” fall away some distance from the muzzle, thus giving the grape

shot a longer effective range before it disperses.

Effectiveness

There is an ongoing discussion about the effectiveness of the medieval handgonnes. A lot of people claim the handgonne was a weapon with a mere psychological effect; that the smoke, sound and fire scared enemies, and that the weapon really didn’t have any tactical use. A battlefield is a horrifying place, with death, fear and suffering all over, and even if loud bangs, smoke and the smell of sulphur probably would increase the chaos and confusion, it wouldn’t make a whole lot of difference. Furthermore, soldiers would not have gone into battle time and again with a weapon they didn’t trust, and was just for ”show”, a city would not have bought 500 of them, and the handgonne would not have developed into what it is today. Let’s take a closer look at what a handgonne is really doing.

One of the differences between the handgonne and other ranged weapons of the age is that arrows and crossbow bolts are that the latter do cutting damage, similar to knives or other edged weapons. They harm by puncturing or cutting organs and limbs. The area affected is small, about the size of the arrow head. This means that you have to hit a vital organ or nerve-centre to put an opponent out of action. There is more than one account of people continuing to fight even when pierced by several arrows. The handgonne on the other hand does kinetic damage. The projectile from a handgonne doesn’t pass through the target as easily as an arrow would, and this means it transfers more of its motive energy into what ever is being hit. The motive energy affects a larger area of an opponents body, as it sets the fluids and fat in the human organism in vibrating motion, which in quite a few instances can injure vital organs. How big an area affected depends of the velocity and weight of the projectile – the higher the weight and speed, the worse the effect.

The usual way to evaluate the damage done by modern firearms is to see how many joule of energy it transfers into its target. The higher the amount of transferred energy, the bigger the damage to the tissues of the body. Tests have shown that the energy transferred by a handgonne is about 1000 joule – a modern assault rifle transfers about 1100. Handgonnes also worked like a charm against the armour of professional soldiers and knights. As these were mainly adapted to cope with arrows and sharp weapons, the sheer power of a projectile from a handgonne would strike an unlucky target to the ground, and with great possibility severely injure him, or at least make him unable to continue the fight.

To have a closer look at how effective handgonnes really were, visit Ulrich Bretscher’s page about handgonnes.

Range and accuracy

Surely, the short barrelled handgonnes would not outshoot a longbow? Perhaps not. The above mentioned Middelaldercenter did some scientifically recorded test firing of a replica of the Swedish Loshultbössan in 2002. It was fired several times with different kinds of gunpowder, based on the recipes above. Also, some shots were fired with modern gunpowder. Different projectiles were used; the handgonne was loaded with 50g of gunpowder, and fired at an angle of 40 degrees. The range of the shots averaged between 600 metres up to 950 metres. Two shots travelled over a 1000 metres, with 1100 being the longest, using modern gunpowder. The muzzle velocity was between 150-250 metres per second. This shows that handgonnes could match longbows as far as range is concerned.

The accuracy of the early firearms might not be excellent, but not totally worthless either. According to Ulrich Bretscher’s experiments, an inexperienced hand gunner would score about 80% hits at a man sized target at a distance of 25 metres, but as the weapons fire a round projectile with the help of non consistent gunpowder from a short barrel, the conditions for marksmanship is limited at the least. The handgonnes, however, seems to have been used mainly in greater engagements, where the target was not an individual but a couple of hundreds in a unit. Even a blind shooter would probably hit someone in a unit of hundreds of spearmen.

From the early examples to later specimens

So what do we know about this? To be honest, not a whole lot, especially when we are talking about Scandinavia. This has a lot to do with a great fire in the seventeenth century, when the royal castle of Stockholm was burnt to ashes, along with a huge pile of medieval documents. This forces us to use sources from the rest of Europe. Applying theory, we might be able to get a decent picture.

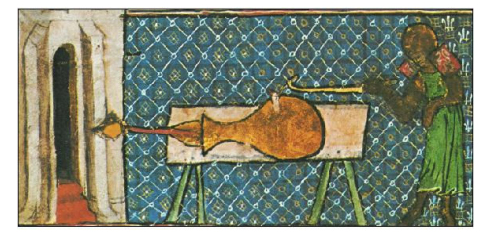

We know that the Europeans have known about black powder since about 1260. Roger Bacon comments on it, but as far as he is concerned, it is only fit for amusement. He is possibly referring to fireworks. In 1326 the Italian city of Florence orders a manuscript (De Nobilitatibus, Sapientis, et Prudentia Regum), written by Walter de Milemete, said to be a member of the English clergy. The text is believed to be copy of an already existing volume, and shows the earliest known picture of a firearm. We see a gunner standing by a vase shaped gun lying on a table. This so called ”pot-de-fer” cannon is loaded with an arrow projectile.

1334 cannons are involved in the defence of Meersburg in south west Germany. Next we hear of an English ship carrying guns in 1338. The battle of Crecy in 1346, also saw guns in action. The guns mentioned above, is with great probability cannons rather than handgonnes. In 1360 the Rathaus of Lübeck explodes, probably due to fault handling of gunpowder. Lübeck was a centre for mercenaries, and as all sorts of Germans, mercenaries and merchants, regularly travelled or even moved to Sweden, the use of gunpowder and it’s companion the handgonne, would have been well known in Scandinavia by the time of the Rathaus explosion. In 1362 the Italian city of Pergua purchase 500 handgonnes, giving us a trace to how many handgonnes were used. In the same year, Kristoffer, the son of the Danish king, Valdemar Atterdag, is struck in the jaw by a projectile believed fired by a handgonne, and dies from it the year after. Ten years later, handgonnes are mentioned in a Danish manuscript, and gunners are employed by the German city of Hamburg from at least 1360. 1395 firearms are first mentioned in Swedish sources, when the Swedes ”borrow” a big gun from the Germans administering the castle in Stockholm.

Gun evolution

The first guns were cast in bronze. They were often vase shaped, and seems to have been used primarily in some sort of mount. They were fired by sticking a burning match or a piece of red hot iron in a priming hole or sometimes in the front end of the gun. Soon guns made of iron staves held together by iron hoops (much like an ordinary barrel) appear alongside the cast bronze guns. Welding is another known method of making guns – you “simply” take a sheet of iron and fold it into at tube, and weld the seams together. Smaller guns were mounted on wooden shafts and used more or less like rifles by ”handgunners”. In England, these devices were referred to as ”hand gonnes”. Some of these weapons was constructed with a hook, allowing the gunner to hook his weapon over a wall or the like, so that the recoil of the handgonne wouldn’t affect him. As some gunners operated single handedly, holding the gun with one hand and the match with the other, this support was surely appreciated. In the latter parts of the fourteenth century cannons with free chambers appear (called Föglare in medieval Swedish). This construction allowed a hugely increased firing rate, as pre-loaded chambers could quickly be inserted in the cannon. Another advantage was that the crew was not as exposed when reloading. Some evidence however, seems to point to these guns not being as reliable as muzzle loaded guns; they were more prone to explode.

1411 the first known triggers appear in sources. They are little more than just an s-shaped or z-shaped lever pivoting around its centre, not unlike crossbow triggers. When pressing the part under the stock, the upper part (holding the match) descends to ignite the primer, firing the handgonne. Some time later, the stock evolves from having been just a stick held under the arm or like a pike, with the end of the stock in the ground, or atop the shoulder, like a bazooka, into a ”real” stock, made to hold against the shoulder. This model coexists with the earlier type. The barrels tend to get longer with smaller calibre.

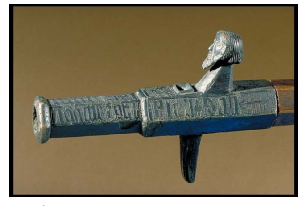

The first known possible handgonne to survive to this day is the so called Loshultsbössan (the Loshult gun/cannon), found in the southernmost part of Sweden. It is a small 31 millimeter bore gun cast in bronze. It is dated to the middle of the fourteenth century, and has been extensively examined by Middelaldercenter i Denmark.

The Loshult gun. It is dated to circa 1340-1350. Note the similarity with the earliest known depicted cannon above

Another gun, Mörköbössan (The Mörkö Handgonne), found south of Stockholm, is dated to the last quarter of the fourteenth century.

A third Swedish handgonne, the Borgholmbössan, will soon be presented on this page.

How were gunners organized?

The above indicates that different forms of gunners have been around in Sweden/Scandinavia since the middle of the fourteenth century, but what it doesn’t tell us, is how common they were. They don’t appear in Scandinavian pictorial evidence until the beginning of the fifteenth century, on the brass of bishop Henrik of Finland (at the time, Finland was called ”the Eastern half of the realm”, an integrated part of Sweden). We have a very vague idea of how gunners were organized, thanks to European sources; the most common seems to have been in groups, like bowmen.

Some examples: At the battle of Ravenspur 1471, 320 Burgundian gunners reportedly participated. John of Burgundy allegedly had 4000 handgonnes in his armoury, and at the battle of Stoke, the earl of Lincoln is said to have fielded 2000 handgonnes! In Scandinavia it is reported that Karl Knutsson in his campaign on Skåne, had enough gunners to organize them into one separate unit, marching under the flag of saint Erik, national saint of Sweden. Karl Knutsson is also reported to have brought ”Wagon guns” (kärrebössor)on the above mentioned campaign.

The naming of guns

Christine de Pisan, a lady who wrote quite a bit on how war was to be waged in the early fifteenth century, clearly states the necessity of naming the guns and cannons. The reason for this, she claims, is that a commander would have a lot of different calibre guns to keep apart, and since the common soldier could not be trusted to remember calibres it was necessary to be able to refer to the gun by its name: ”I would like Katrina placed over here, and Anna placed over there!”. The soldier would then know what gun was which, and what kind of ammunition would go with it.

The most famous guns in Sweden was ”Diefulen” (”The Devil”) and ”Diefuls Mater” (”The Mother of the Devil”), that protected the Stockholm Castle in the sixteenth century. The named handgonnes of Albrechts Bössor is named Örsdöder (Destrier killer), Keterlin Haverblast, Faule Agnes and Mathilda.

The other guns are yet to be named.

This article, written by Johan Käll & Peter Ahlqvist, was previously published on our old webpage.

Swedish medieval armour terminology

Svenska medeltida termer för rustningar

Inom rustningsterminologi såväl som kläder från medeltid råder ibland stor förvirring. Engelska och franska termer samsas tillsammans med lokala termer och latin. Dessutom används termer från hela medeltiden och under 500 år ändrades både rustning och termer. Skillnader i rustning som var uppenbara för dem har gått förlorade för oss. Vi har nu föga aning vad som skiljer en aketon från en gambeson. Nya tolkningar har gjorts som vissa använder sig av, vissa inte. Inom Albrechts Bössor försöker vi värna om den svenska medeltida terminologin och letar med ljus och lykta efter samtida termer. Här följer en liten sammanfattning av något vi funnit.

Tygh

Den medeltida benämningen för krigsmateriel var Tygh, något som i viss mån även gäller även idag. De som gjort värnplikt vet att tygförrådet är det som man hämtar sina vapen ifrån. Detta används i Erikskrönikan ’ok redde sik tha wapn ok tyghe’ på sidan 30.

Pekkilhuvva

Vanligen kallad bascinet. 1350 säljer en viss Niklas Pekkilhuva jord i Kalmar. Hans vapen visar en bascinet med fjällanventail (Raneke, sidan 593).

Även kung Magnus Eriksson var stolt ägare till ” jtem vnam pekkelhwæ. cum slappor.”

Slappor

Uttrycket ’Slappor’ är till viss del höljt i dunkel, men det är mycket sannolikt rör det sig om någon form av skydd för halsen, så som en ringkrage hängande från en hjälm (en så kallad aventail) eller en lös halskrage av läder, tyg, ringbrynja eller lameller.

Plata

En rustning för bålen bestående av stål- eller järnplattor nitade på insidan av läder eller tyg. Även kallad coat of plates, Visbyharnesk eller överdragsrustning. Erikskrönikan nämner dessa många gånger: ”mahrg plata bleff ther ospent” (sidan 57), “hielma plator och panzere” (sidan 30), ”min hielm min brynia ok min plata” (sidan 37), ”harnisk plator ok anat meer” (sidan 106) för att nämna några exempel. Även Kung magnus hade en, fast han hade glömt den i Norge: ”et vna platæ remansit in akersborgh.”

Panzar

En tygrustning, att ha under annan rustning eller för sig själv. Kallas annars gambeson eller aketon. Erikskrönikan kallar den panzar eller panzare; “hielma plator och panzere” (sidan 30). Att den nämns tillsammans med platan visar att den inte bara är ’ett pansar’ utan något speciellt sådant. Under denna tid används bara plata, brynja och tygrustningar vad man vet. Kung Magnus Eriksson hade förutom ovan nämnda rustningstyper ”jtem vnum panzer”. Ett senare omnämnade av panzare finns i Stockholms tänkebok från 1400-talet.

Kittelhatt/Järnhatt

Det finns många omnämnanden om denna hjälm som i olika former lever kvar än idag. Järnhatten var mycket vanlig och kan enklast beskrivas som en järnkalott med brätte. Järnhatten är den hjälm de medeltida landslagarna säger att folkuppbådet skall ha.

Muzza

Den vanligaste tolkningen av muzza eller muza är att det rör sig om en ringbrynjehuva, en huva av ringbrynja som vanligtvis bärs under en annan hjälm. Det påminner mycket om hur ”mössa” stavas under 1300-tal i olika dokument. Muzzan var en del av den rustning folkuppbådet skulle ha. En riddare vid namn Anders testamenterar 1299 även sin ”cum sella muzam cum plata” Senare skall hans ”armatorum” (rustning) säljas för att ge pengarna till hans biktfar. Muzam var alltså inte del av rustningen, som troligen var en ringbrynja vid denna tid.

Brynia/Malia/malioharnisk

Ringpansar, ringbrynja. Ordet nämns ofta i källorna, till exempel i Erikskrönikan: ”min hielm min brynia ok min plata” (sidan 37), i Karl Magnus (sidan 255) ”oc före han i twa brynior” eller i Riddar Ivan – Lejonriddaren (sidan 50) “brynior ok hiälma the sunder slitu”. Rustningstypen benämns malioharnisk i ett brev från 1408: ”för en fating och ena plato och för ett malaharnisk, som han hadhe lanth wårom fadher”

Kung Magnus ägde även ”jtem I. par maliotygh ” och ”I. par maliohuso”.

Harnisk

Harnisk är ett något luddigt uttryck. I Erikskrönikan talar man om ”harnisk plator ok anat meer” (sidan 106), ”man saa ther margt eth harnisk blangt” (sidan 117), något som antyder att ett harnisk var gjort av (putsad metall). Kanske rör det sig om tidiga plåtrustningar för bålen. Ordet kopplas också samman med andra rustningsdelar. I Raven von Barnekows räkenskaper för Nyköpingshus står att Kung Albrecht köper ’benharnesk’ för 4 öre. Kanske är det så att harnisk är en samlingsterm för rustningsdelar i plåt? Detta motsäges av termen Malaharnisk (mala/malia/malja, ring) som nämns i ett brev. Kanske är det bara ett allmänt ord för rustning.

Andra termer

Kopartygh – Hästrustning

Tasteer – Stjärn, skydd för hästens huvud

Båda dessa enligt tolkningar är gjorda av Sven-Bertil Jansson. Han tolkar passagen på sidan 106 i Erikskrönikan. Dessutom nämns begreppen i ovan nämnde riddar Anders testamente: ”confero dextrarium meum cum cuparthyr taster”.

Undersökningsunderlag

Svenskt diplomatarium

Danskt Diplomatarium

Medeltida romaner 1300-tal

Erikskrönikan

Ivan Lejonriddaren

Karl Magnus

Flores ok Blanzeflor

Medeltida dokument 1300-tal

Raven von Barnekows räkenskaper för Nyköpings Fögderi

Om Koningx Styrilsi

Magnus Erikssons Landslag

Övrigt

Raneke/Svenska Medeltidsvapen III

Kung Magnus boupteckning för Bohus slott

Karl Magnus, en roman från sent 1300-tal

Ivan Lejonriddaren

Den här artikeln, skriven av Johan Käll, var tidigare publicerad på vår gamla hemsida i annan version.

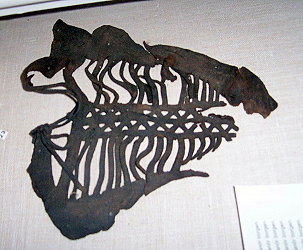

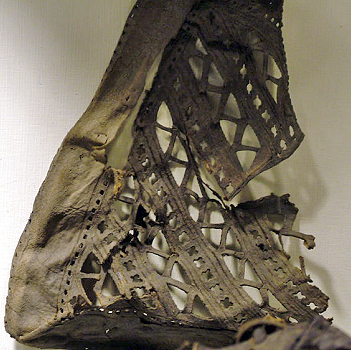

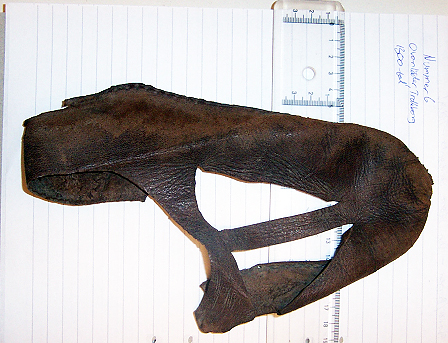

Some shoes from medieval Sweden

This is merely a a list of some photographs of shoes we have encountered in different museums in Sweden. The shoes used in Sweden was not very different from shoes in the rest of Europe, at least not that we can see from archaeological evidence. In the salary for people working in farms during 14th century usually three pairs of shoes and a pair of pattens a year was included, along with food and boarding.

Boots

Some rough shoes for use in less civilised areas.

Fancy shoes

No reason you can not have fancy shoes just because you live in a barbaric country is there? The Swedes were trying to be part of continental fashion too.

Other shoes

Written by Johan Käll & Peter Ahlqvist

German daggers uncovered

I just found an article about a heap of daggers unearthed in north German city of Stralsund. It just so happens, some of us are going to Stralsund next Friday. Perhaps we could get a closer look at the excavations, if they are still at it?

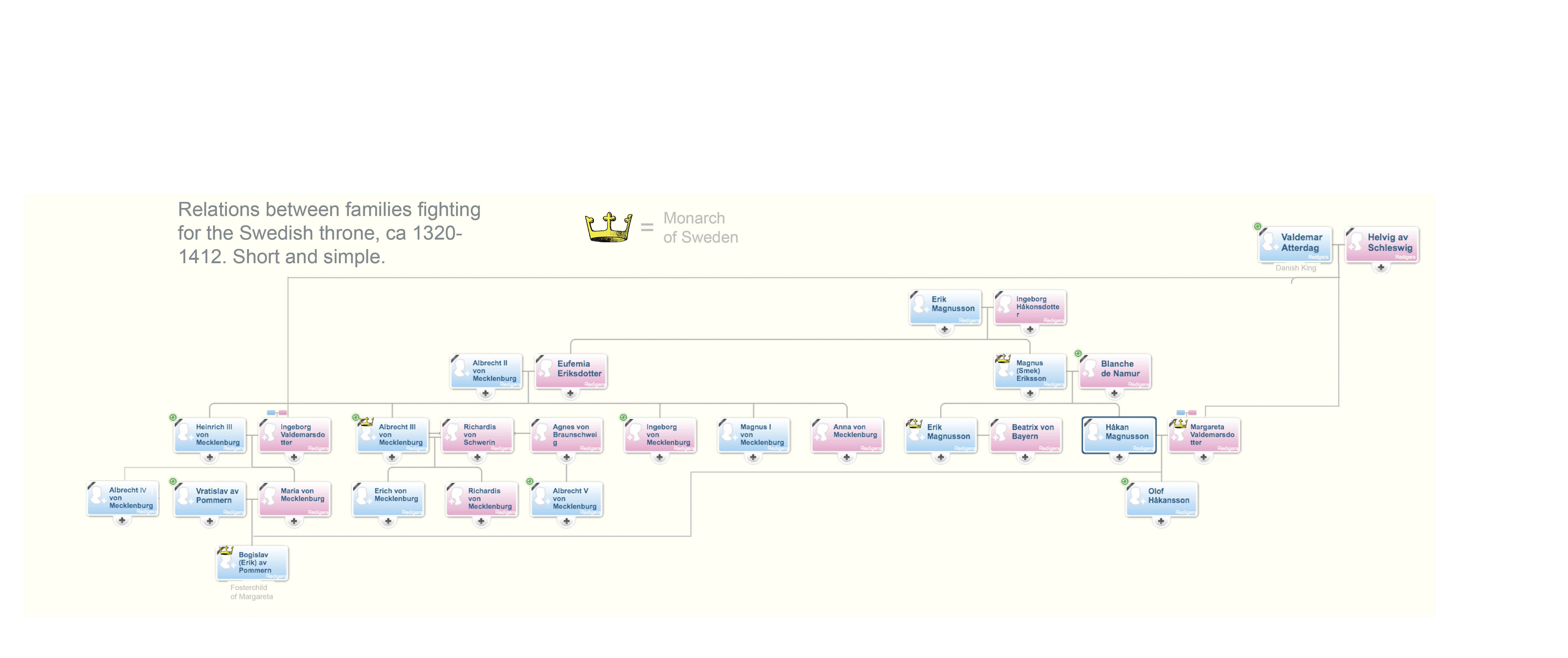

Family tree of Swedish royals during the 14th century

When you are trying to understand the battle of the crown in 14th century Sweden, you will pretty soon be quite mixed up in relations. This family tree is simplified to show which people held keep positions in the struggle.

In short, ”our” king Albrecht was king Magnus Eriksson’s sister’s son, which meant he could make a (kind of) legitimate claim for the throne. Margareta Valdemarsdotter was married to Håkan Magnusson, Magnus Eriksson’s son, which meant her son Olof Håkansson could make a (kind of) legitimate claim for the throne. When he died at the age of 17, Margareta adopted her sister Ingeborg Valdemarsdotter’s grandson, Bogislav of Pomerania (who was also the grandson of ”our” Albrecht’s brother), which meant that he could claim the throne. Legitimate? Well, you tell me… That was the short version. The more elaborate story begins in this post.

We have chosen to be extra specific when it comes to king Albrecht’s immediate family (his name on this image is Albrecht III von Mecklenburg). Other characters of note is the strongheaded duchess Ingeborg Håkansdotter, mother of king Magnus Eriksson and self-appointed ruler of the realm, and her husband, the duke Erik Magnusson, who was put in a tower to starve to death by his brother Birger. Also, there is Håkan Magnusson – king of Norway and faithful son of king Magnus (not to mention king Erik Magnusson – the unfaithful son of king Magnus). Also, have a special look at the foster relation between Bogislav of Pomerania (to the far left) and his grandmother’s sister – queen Margareta of Denmark; the duo ruled Sweden after the defeat of king Albrecht, and when Margareta died, Bogislav ruled the entire Kalmar union.

Click the image to view a bigger version. We apologize for the colors, which look like they have been stolen from a nursery from the 1960’s…

This page might make more sense together with the following pages:

Timeline of Swedish politics 1306-1412

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 1 – The beginning

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 2 – The struggle of the lawmaker

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 3 – The age of the king

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 4 – Defeat and union

Who was Albrecht of Mecklenburg?

A 14th century political history of Sweden, part 4 – Defeat and union

Winds of war

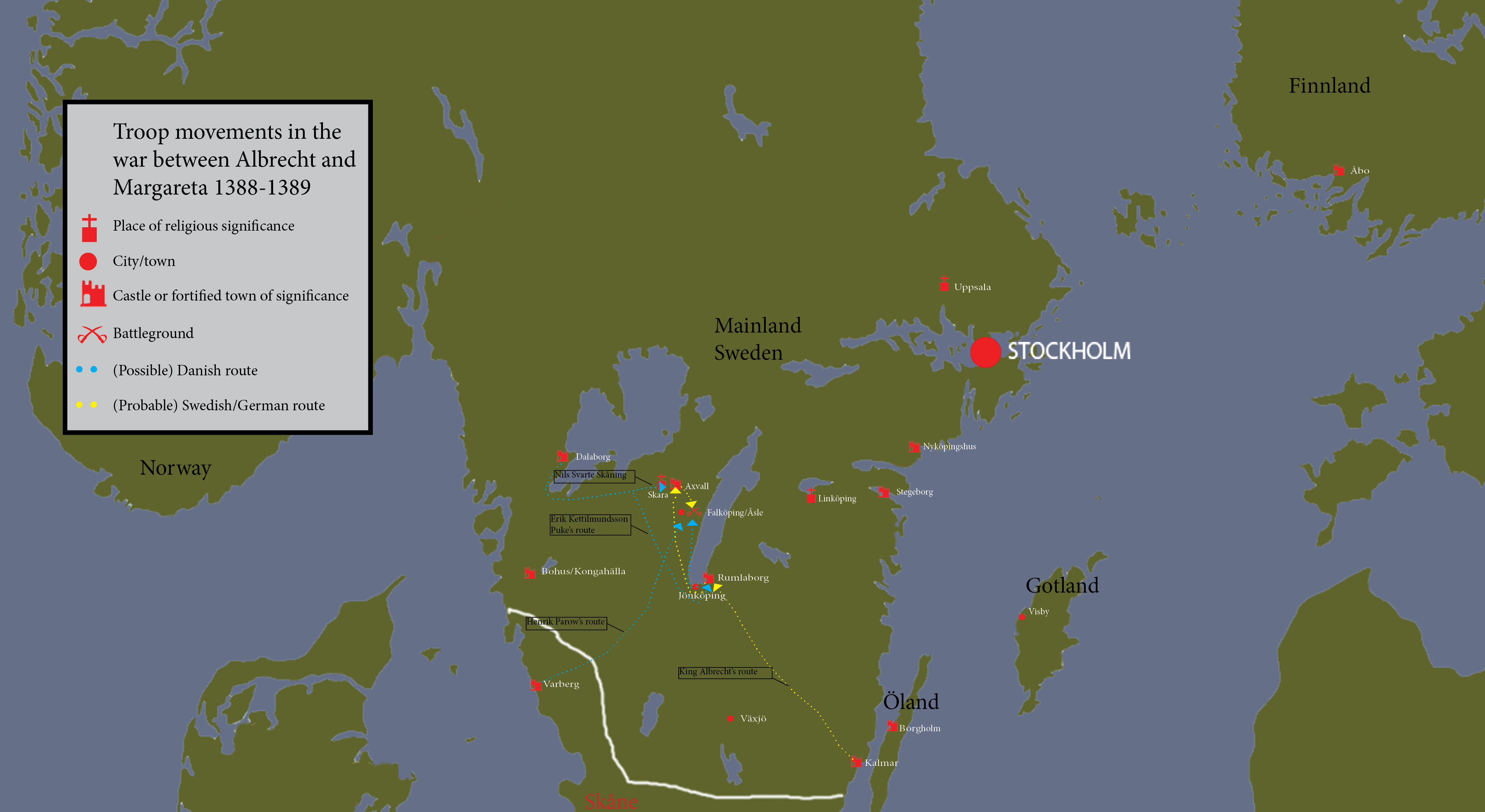

After the meeting at Dalaborg, Margareta starts to gather an army to fight the king, But Albrecht is not sitting idle. He makes the burghers of Stockholm renew their oath of fealty to him and departs for Germany to muster troops. Margareta is ahead of him, and with an army of Swedes her supporters besiege the stronghold of Axvalla. It is too strong to take by storm, and a long siege lead by Nils Svarte Skåning begins. The main part of the army marches on, under the command of Erik Kettilsson Puke (whose name has got nothing to do with throwing up).

Around new year 1389 Albrecht returns to Sweden with a host of men. He disembarks at Kalmar and march on Axvall. On the way there, he passes the south peak of lake Vättern, and manage to liberate the besieged Rumlaborg. When he reaches Axvall he also receives word that a Danish army, under the command of his old retainer Henrik Parow has been marching from Halland and is about to join the army of Erik Kettilsson Puke. Albrecht turn south to face the two armys, and the 24th of february they meet outside the village of Åsle, in the vicinity of Falköping.

The chronicler Detmar describes it like this:

In deme jare Cristi 1389, in sunte Mathias dage, was grot strid in Sweden bi Axewalde. De koninghinne van Norwegen hade dar sand wol vifteynhundert gewapent. Der hovetman was en riddere, de heet her Hinrik Parowe.

On this day of Christ 1389, in saint Matthew’s day, it was a great battle in Sweden by Axvall. The queen of Norway had sent a good fifteenhundred armed. The commander was a knight that was called Henrik Parow.

Henrik Parow’s troops take a defensive position flanked by a mountain and a marshland, which also stretches in front of his lines. Albrecht is eager to engage, and he is certain of victory; his host consists of glorious German knights and trained mercenaries. But everyone is not as sure as he is. Tradition tells us that an old knight called Tyke Olofsson asked the king to refrain from attacking, or at least try to negotiate the marshland before charging. ”We do not want to fight the Dane this day – it won’t do us any good.” he concluded, but the king wouldn’t listen. Even though some of his men weren’t ready, he lead his knights, including the bishop of Skara, his cousins and the counts of Ruppin and Holstein, on a charge across the frozen land and at first he was very successful: he ”conquered two banners”. But the battle would not go his way. One of his commanders, Gerhard Snakenborg, turned and fled the battlefield with 60 riders, and others is said to have stuck in the boggy ground.

In less than two months, through snow and during very harsh conditions, king Albrecht’s army marched over 300 kilometers – and had time to stop and liberate Rumlaborg before fighting at Åsle

The king was taken captive along with his son, prince Erich, and as they were taken from the field of battle by their captors, they passed Tyke Olofsson. The king cried out to him: ”Old man! Old man! Why didn’t I listen?” The battle of Åsle is a decisive victory for the rebels, but their commander, Henrik Parow, is killed. When the queen learns of the victory she rides to Bohus where she and her supporters celebrate their victory. The king and his son are eventually taken to Skåne and the castle of Lindholmen, where they are being held captive.

German resistance

Even though Margareta managed to beat her enemy at the battlefield, her fight for dominion of Sweden was far from over. Although she conquers Kalmar, Rumlaborg and Axvall, Stockholm is still in German hands, and the burghers of the city refuse to give up the fight. They are being supported by the Hansa, which send warships to commandeer ships belonging to the supporters of Margareta. They also bring food and soldiers to the besieged Stockholm. On a different note, these ships, crewed by knights, burghers, soldiers and peasants, according to Detmar, later cause much trouble on the Baltic sea as pirates (so called Vitalianer). As they are allowed to enter the harbours of the Mecklenburgish Wismar and Rostock, other Hansa cities, which suffered economic losses due to pirate attacks, started to lose interest in the conflict between the Mecklenburgish dukes that supported Albrechts and the queen Margareta. Nevertheless, some of the Hanseatic towns, Rostock among some others, make alliances with noblemen and other cities to try to force Margareta into releasing Albrecht; among other things they try to enforce a trade embargo against Margareta. But their efforts are of little use. Some, like the old Albrecht-loyal knight Vicke van Vitzen even sells his estates to Margareta and swear loyalty to her. He was not the only one to do so.

The aggressive Vitalianer pirates put a hamper on trade in the Baltic sea. Many ships were just anchored as the risk of sailing was too great

In 1393 the conflict is putting a big hamper on trade in the Baltic sea, not least because of the Vitalianer. Margareta met with representatives from the Hansa and king Albrecht’s nephew Johann in Falsterbo at the end of September. At this meeting it was agreed that Albrecht and his son should be let free from captivity for a couple of years, until the parties had reached an acceptable agreement. As security, the city of Stockholm was to be handed over to four honest men, which should let Margareta occupy it if the king refused to go back to captivity after the said time.

The war goes on – but so does the negotiations

In July 1394 everyone finally seemed to agree. The king and his son had been imprisoned for more than five years, and the king himself probably knew that his days as king of Sweden were numbered. He was to be released against a huge ransom of 60 000 marks of silver (the old king Magnus bought the entire province of Skåne for about half as much in the 1330’s), and if that sum wasn’t paid back in six months, the king and his son should return into captivity, or the queen would be entitled to occupy Stockholm. At the same meeting, Margareta and the Hansa also agreed on taking actions against the Vitalianer, as they were still a serious problem for great parts of northern Europe. During the 1390’s tremendous efforts were put on ridding the Baltic sea from pirates. Several fleets with several thousand men hunted the Vitalianer and drove them from whatever harbors the controlled.

The final negotiations for the king’s release took place at Lindholmen were king Albrecht and his son had been spending their time since the defeat at Åsle. The 26th of September 1395 it is decided that Albrecht and his son should be released for a period of three years (until the 29th of September 1398), during which time they should try to raise the enormous ransom. If he succeeded, he wasn’t allowed to wage war on Margareta for at least a year. If he didn’t succeed, he could go back to prison but break the peace in nine weeks, or he could simply let Margareta have Stockholm and the peace should be everlasting. Albrecht was released in Helsingborg at the end of September 1395, about a month after Stockholm was entrusted to the Hanseatic cities (read more here) of Königsberg, Elbing, Thorn, Danzig, Reval, Greifswald, Lübeck and Stralsund, as a kind of peace keeping force, while Albrecht and Erich started to round up the money needed for the ransom. Their efforts was however in vain, and in 1398 the cities’ representatives leave Stockholm, allowing Margareta to occupy the city. The conflict between king Albrecht and Margareta is definetely over.

Today the castle of Lindholmen is nothing more than a grassy mound, but in the 14th century it was one of the most important castles in the entire Danish realm

A free man

Albrecht returned to his Mecklenburg of old and ruled the land for years. In a letter dated 25th of November 1405, in the end, he was able to forgive the peoples of Sweden, Norway and Denmark for what evil they had bestowed upon him. The same date he also writes other letters, in which he states that he will no longer claim Swedish regions, but rather support his son, duke Erich. Albrecht dies 1412, and with him dies the Mecklenburg dynasty’s hopes for the Swedish throne.

Margareta, Bogislav and the Kalmar union

Margareta, her adoptive son Bogislav, the Swedish council and many other Swedish nobles were gathered in 1396 to the recess of Nyköping, which in short meant that the crown reclaims all estates and all land that has been given or claimed since 1363, when king Albrecht came to power. All strongholds an castles that was built during those years should be torn down if the queen so wished. But that wasn’t all that was discussed. The most important thing at the meeting was that the congregated potentates agreed that none of the three Nordic realms should wage war on oneanother. They had ”in all these kingdoms one lord and king”. The young Bogislav of Pomerania could look forward to a splendid position as king over a great realm.

He was crowned in 1397, and at the same time the Kalmar union was signed between the three kingdoms. The statutes of the union stipulated, among other things, that the descendants of the king should inherit the crown – a direct dichotomy to the Landslag, accepted in the middle of the 14th century. Also, each country should have right to their own laws, but at the same time they should henceforth be seen as one kingdom – under ine king. Margareta was still holding the reins until 1400 when Bogislav came of age and at least formally took over power from his mother. He reigned the new union between 1400-1439 with two interludes. He was however forced to change his name into the more proper Swedish name Erik – Bogislav was too strange a name for the Scandinavians.

1400 Erik came of age, and rode his Eriksgata the following year, but his mother was still holding most of the power; she was in no way willing to let go of her influence.

In 1402 Margareta negotiated with Henry IV of England to be able to marry Erik with Henry’s daughter Philippa. The negotiations went well, and Erik and Philippa was married in Lund 1406.

He, his young queen and his mother worked hard to strengthen the three kingdoms against first and foremost the Germans, in the form of the Hansa and the Teutonic order. Their measures included instating foreign vasalls to control Sweden, which eventually lead to unrest amongst the population.

Before that, however, they declared war in the Hansa, as they considered the trade confederation too powerful. On the side of the Hansa, the Holsteiners joined, and the Baltic region was thrown into a war that lasted until 1435, with some armistices.

Margareta died the 28th of October 1412, when negotiating for the city of Flensburg, which had been seized by the Holsteiners. She is buried in a magnificent sarcophagus in Roskilde cathedral in Denmark. Curiously enough, king Albrecht died the same year, the 31st of March or 1st of April. He was laid to rest alongside Richardis in the Doberaner Münster in Bad Doberan of the Mecklenburg area.

This article was written by Peter Ahlqvist.