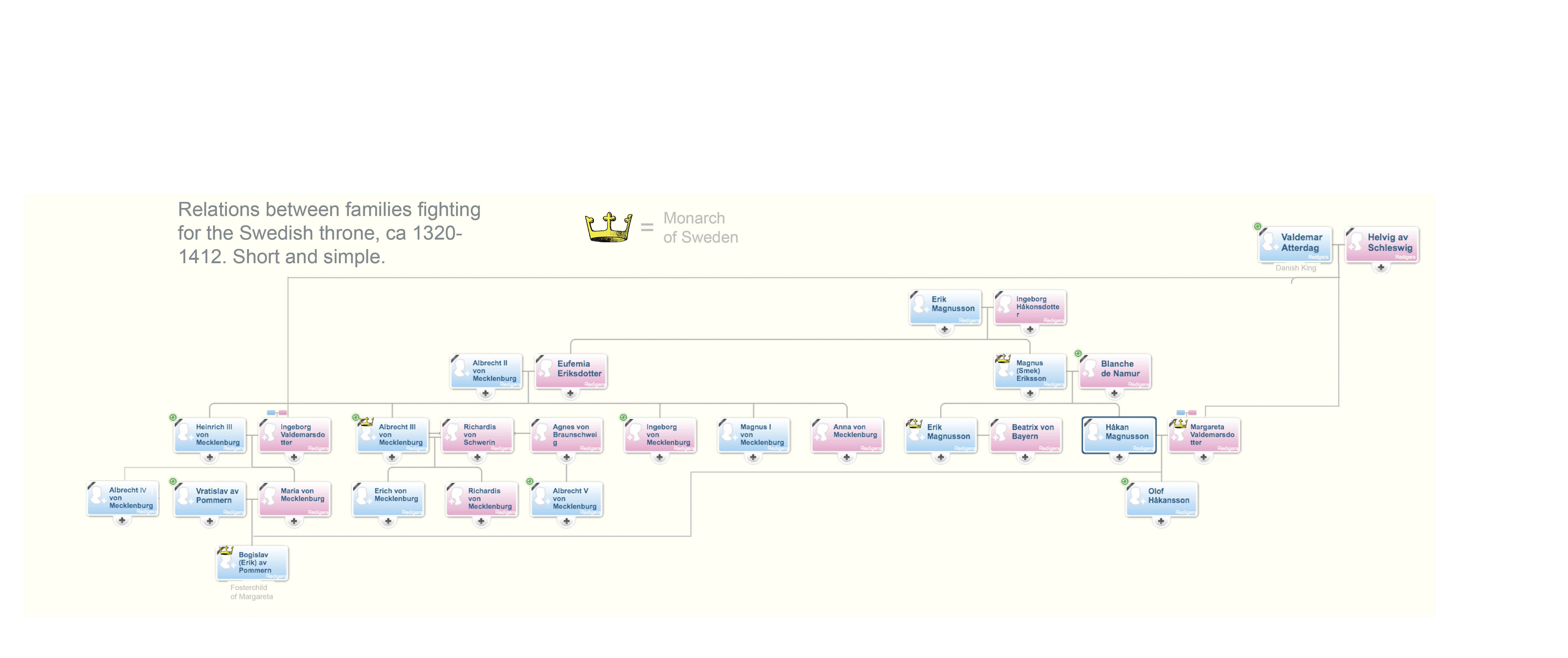

We could start this text by telling you about the Chinese origin of black powder, as can be found on dozens of pages on the web. But we won’t, because it’s not relevant. This article is about the use of handgonnes and black powder during the European middle ages, and that is a whole other thing. So we’ll start at black powder as a phenomenon.

Gunpowder

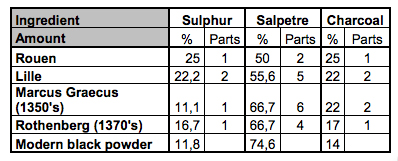

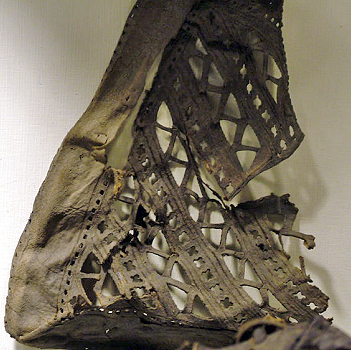

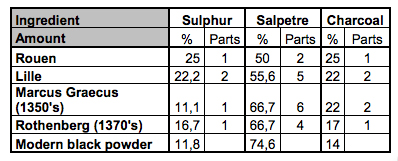

In medieval Sweden gunpowder was called just ”pulver”, wich translates into ”powder”. There are quite a few old powder recipes still around, and the ones that suits our selected historical period

are referred to as, for example, Rouen, Lille, Rothenburg and Marcus Graecus. They all use the same ingredients, but the amounts differ. In the table below, they are compared to a modern ”perfect”

gunpowder.

Tests made at the Middelaldercenter in Nyköbing, Denmark show a correlation between higher muzzle velocity and higher amount of salpetre. The ingredients were ground up and mixed, resulting in a so called dry mixed powder. This can be used as it is, but it will be more effective if mixed with alcohol, shaped into bars or pellets and then ground again, producing wet mixed powder or meal powder. The alcohol dissolves the salpetre, and lets the tiny sulphur crystals divide and evenly on the grains of charcoal, making the powder burn more even. It is important to note that there has

been some debate about the use of alcohol in medieval gunpowder, as distilled beverages is barely known at the time. However, sources speak of a ”Henricus Brännewattnmakare” (Henricus, maker of burnt (distilled) water, meaning a producer of alcohol) in the city of Lund in the 1350’s, wich means that alcohol was in use at the time. If it was used to make gunpowder we do not know. Sulphur could be collected in volcanic areas in Iceland or Italy, while salpetre was produced by collecting dung and urine from livestock, and processing it, to extract the salpetre. Charcoal was abundant in medieval society.

Bössa?

The name of our group contains the word ”Bössor”, and in modern Swedish ”Bössor” means some sort of handgun like a rifle or shotgun. In the middle ages the term ”bössa” (sg.)/”bössor” (pl.) is applied to both handgonnes and cannons. In other words there are two different types of ”Bössor” in the fourteenth century, and it can be used as a very rough measurement regarding calibre and purpose; ”Stenbössa” – firing stones, and ”Lodbössa” – firing lead shot. The ”Stenbössa” seems to stand for larger calibre – possibly a cannon, whilst the ”Lodbössa” seems to have had smaller calibre – possibly a handgonne.

The projectile

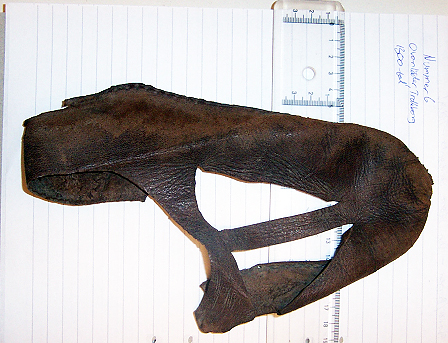

The handgonne and the medieval cannon fired mainly lead shot (”lod”), stone balls, ”grape shot” or arrows. The use of arrows is a bit peculiar – it doesn’t seem to have any obvious advantages in comparison to stone balls. One theory is that the cannon presented an alternative to the so called ballista (a siege engine for firing huge arrows), and that gunpowder was just another method of propelling the projectile. The lead shot was probably cast by the gunner himself, using a cast made of sand stone, soap stone or bronze – as there was no fixed system for calibre, each man had to provide for himself.

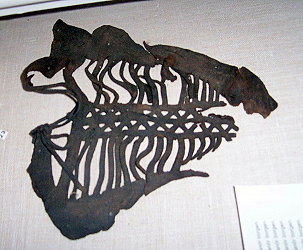

A mould for casting lead bullets. From the National museum in Helsinki

The grape shot (Swe: kartesch) , which turned the handgonne or cannon into sort of a shotgun, was used against people and animals (like war horses) at close range. Virtually anything could be used as grapeshot, but shards of flint seem to have been common, as the razor sharp flint shards inflicted massive damage. The grape shot could be free loaded, or put into a triangular container for bigger guns; the Museum of Medieval Stockholm displays some of these, found on a sunken ship. When fired, the walls of the ”pyramid” fall away some distance from the muzzle, thus giving the grape

shot a longer effective range before it disperses.

15th-16th century grapeshot containers filled with flint

Effectiveness

There is an ongoing discussion about the effectiveness of the medieval handgonnes. A lot of people claim the handgonne was a weapon with a mere psychological effect; that the smoke, sound and fire scared enemies, and that the weapon really didn’t have any tactical use. A battlefield is a horrifying place, with death, fear and suffering all over, and even if loud bangs, smoke and the smell of sulphur probably would increase the chaos and confusion, it wouldn’t make a whole lot of difference. Furthermore, soldiers would not have gone into battle time and again with a weapon they didn’t trust, and was just for ”show”, a city would not have bought 500 of them, and the handgonne would not have developed into what it is today. Let’s take a closer look at what a handgonne is really doing.

One of the differences between the handgonne and other ranged weapons of the age is that arrows and crossbow bolts are that the latter do cutting damage, similar to knives or other edged weapons. They harm by puncturing or cutting organs and limbs. The area affected is small, about the size of the arrow head. This means that you have to hit a vital organ or nerve-centre to put an opponent out of action. There is more than one account of people continuing to fight even when pierced by several arrows. The handgonne on the other hand does kinetic damage. The projectile from a handgonne doesn’t pass through the target as easily as an arrow would, and this means it transfers more of its motive energy into what ever is being hit. The motive energy affects a larger area of an opponents body, as it sets the fluids and fat in the human organism in vibrating motion, which in quite a few instances can injure vital organs. How big an area affected depends of the velocity and weight of the projectile – the higher the weight and speed, the worse the effect.

The usual way to evaluate the damage done by modern firearms is to see how many joule of energy it transfers into its target. The higher the amount of transferred energy, the bigger the damage to the tissues of the body. Tests have shown that the energy transferred by a handgonne is about 1000 joule – a modern assault rifle transfers about 1100. Handgonnes also worked like a charm against the armour of professional soldiers and knights. As these were mainly adapted to cope with arrows and sharp weapons, the sheer power of a projectile from a handgonne would strike an unlucky target to the ground, and with great possibility severely injure him, or at least make him unable to continue the fight.

To have a closer look at how effective handgonnes really were, visit Ulrich Bretscher’s page about handgonnes.

Range and accuracy

Surely, the short barrelled handgonnes would not outshoot a longbow? Perhaps not. The above mentioned Middelaldercenter did some scientifically recorded test firing of a replica of the Swedish Loshultbössan in 2002. It was fired several times with different kinds of gunpowder, based on the recipes above. Also, some shots were fired with modern gunpowder. Different projectiles were used; the handgonne was loaded with 50g of gunpowder, and fired at an angle of 40 degrees. The range of the shots averaged between 600 metres up to 950 metres. Two shots travelled over a 1000 metres, with 1100 being the longest, using modern gunpowder. The muzzle velocity was between 150-250 metres per second. This shows that handgonnes could match longbows as far as range is concerned.

The accuracy of the early firearms might not be excellent, but not totally worthless either. According to Ulrich Bretscher’s experiments, an inexperienced hand gunner would score about 80% hits at a man sized target at a distance of 25 metres, but as the weapons fire a round projectile with the help of non consistent gunpowder from a short barrel, the conditions for marksmanship is limited at the least. The handgonnes, however, seems to have been used mainly in greater engagements, where the target was not an individual but a couple of hundreds in a unit. Even a blind shooter would probably hit someone in a unit of hundreds of spearmen.

From the early examples to later specimens

So what do we know about this? To be honest, not a whole lot, especially when we are talking about Scandinavia. This has a lot to do with a great fire in the seventeenth century, when the royal castle of Stockholm was burnt to ashes, along with a huge pile of medieval documents. This forces us to use sources from the rest of Europe. Applying theory, we might be able to get a decent picture.

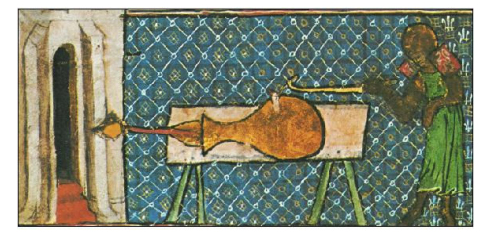

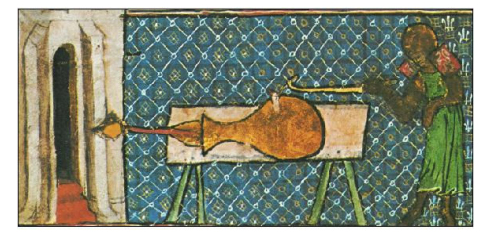

We know that the Europeans have known about black powder since about 1260. Roger Bacon comments on it, but as far as he is concerned, it is only fit for amusement. He is possibly referring to fireworks. In 1326 the Italian city of Florence orders a manuscript (De Nobilitatibus, Sapientis, et Prudentia Regum), written by Walter de Milemete, said to be a member of the English clergy. The text is believed to be copy of an already existing volume, and shows the earliest known picture of a firearm. We see a gunner standing by a vase shaped gun lying on a table. This so called ”pot-de-fer” cannon is loaded with an arrow projectile.

The earliest known European image of a firearm. Circa 1320

1334 cannons are involved in the defence of Meersburg in south west Germany. Next we hear of an English ship carrying guns in 1338. The battle of Crecy in 1346, also saw guns in action. The guns mentioned above, is with great probability cannons rather than handgonnes. In 1360 the Rathaus of Lübeck explodes, probably due to fault handling of gunpowder. Lübeck was a centre for mercenaries, and as all sorts of Germans, mercenaries and merchants, regularly travelled or even moved to Sweden, the use of gunpowder and it’s companion the handgonne, would have been well known in Scandinavia by the time of the Rathaus explosion. In 1362 the Italian city of Pergua purchase 500 handgonnes, giving us a trace to how many handgonnes were used. In the same year, Kristoffer, the son of the Danish king, Valdemar Atterdag, is struck in the jaw by a projectile believed fired by a handgonne, and dies from it the year after. Ten years later, handgonnes are mentioned in a Danish manuscript, and gunners are employed by the German city of Hamburg from at least 1360. 1395 firearms are first mentioned in Swedish sources, when the Swedes ”borrow” a big gun from the Germans administering the castle in Stockholm.

Gun evolution

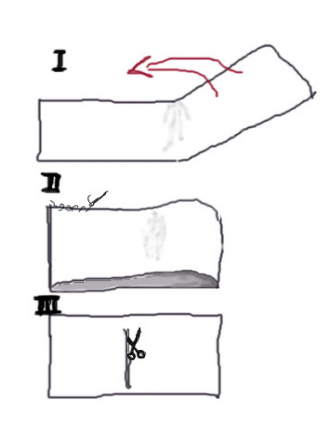

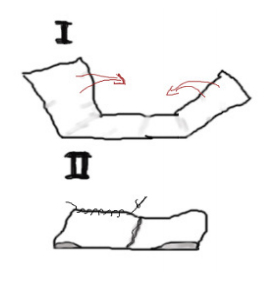

The first guns were cast in bronze. They were often vase shaped, and seems to have been used primarily in some sort of mount. They were fired by sticking a burning match or a piece of red hot iron in a priming hole or sometimes in the front end of the gun. Soon guns made of iron staves held together by iron hoops (much like an ordinary barrel) appear alongside the cast bronze guns. Welding is another known method of making guns – you “simply” take a sheet of iron and fold it into at tube, and weld the seams together. Smaller guns were mounted on wooden shafts and used more or less like rifles by ”handgunners”. In England, these devices were referred to as ”hand gonnes”. Some of these weapons was constructed with a hook, allowing the gunner to hook his weapon over a wall or the like, so that the recoil of the handgonne wouldn’t affect him. As some gunners operated single handedly, holding the gun with one hand and the match with the other, this support was surely appreciated. In the latter parts of the fourteenth century cannons with free chambers appear (called Föglare in medieval Swedish). This construction allowed a hugely increased firing rate, as pre-loaded chambers could quickly be inserted in the cannon. Another advantage was that the crew was not as exposed when reloading. Some evidence however, seems to point to these guns not being as reliable as muzzle loaded guns; they were more prone to explode.

1411 the first known triggers appear in sources. They are little more than just an s-shaped or z-shaped lever pivoting around its centre, not unlike crossbow triggers. When pressing the part under the stock, the upper part (holding the match) descends to ignite the primer, firing the handgonne. Some time later, the stock evolves from having been just a stick held under the arm or like a pike, with the end of the stock in the ground, or atop the shoulder, like a bazooka, into a ”real” stock, made to hold against the shoulder. This model coexists with the earlier type. The barrels tend to get longer with smaller calibre.

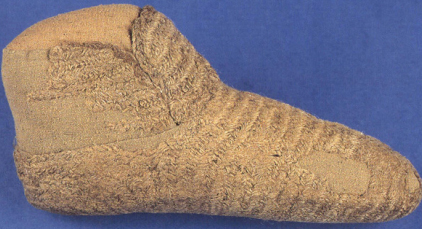

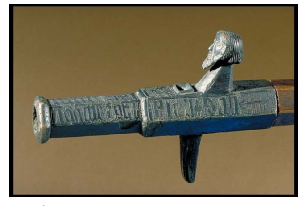

The first known possible handgonne to survive to this day is the so called Loshultsbössan (the Loshult gun/cannon), found in the southernmost part of Sweden. It is a small 31 millimeter bore gun cast in bronze. It is dated to the middle of the fourteenth century, and has been extensively examined by Middelaldercenter i Denmark.

The Loshult gun. It is dated to circa 1340-1350. Note the similarity with the earliest known depicted cannon above

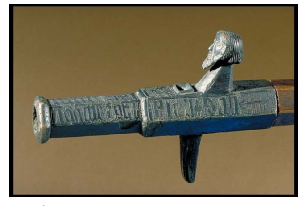

Another gun, Mörköbössan (The Mörkö Handgonne), found south of Stockholm, is dated to the last quarter of the fourteenth century.

The beautiful and unique Mörkö handgonne, dated to circa 1380-1400

A third Swedish handgonne, the Borgholmbössan, will soon be presented on this page.

How were gunners organized?

The above indicates that different forms of gunners have been around in Sweden/Scandinavia since the middle of the fourteenth century, but what it doesn’t tell us, is how common they were. They don’t appear in Scandinavian pictorial evidence until the beginning of the fifteenth century, on the brass of bishop Henrik of Finland (at the time, Finland was called ”the Eastern half of the realm”, an integrated part of Sweden). We have a very vague idea of how gunners were organized, thanks to European sources; the most common seems to have been in groups, like bowmen.

Some examples: At the battle of Ravenspur 1471, 320 Burgundian gunners reportedly participated. John of Burgundy allegedly had 4000 handgonnes in his armoury, and at the battle of Stoke, the earl of Lincoln is said to have fielded 2000 handgonnes! In Scandinavia it is reported that Karl Knutsson in his campaign on Skåne, had enough gunners to organize them into one separate unit, marching under the flag of saint Erik, national saint of Sweden. Karl Knutsson is also reported to have brought ”Wagon guns” (kärrebössor)on the above mentioned campaign.

The naming of guns

Christine de Pisan, a lady who wrote quite a bit on how war was to be waged in the early fifteenth century, clearly states the necessity of naming the guns and cannons. The reason for this, she claims, is that a commander would have a lot of different calibre guns to keep apart, and since the common soldier could not be trusted to remember calibres it was necessary to be able to refer to the gun by its name: ”I would like Katrina placed over here, and Anna placed over there!”. The soldier would then know what gun was which, and what kind of ammunition would go with it.

The most famous guns in Sweden was ”Diefulen” (”The Devil”) and ”Diefuls Mater” (”The Mother of the Devil”), that protected the Stockholm Castle in the sixteenth century. The named handgonnes of Albrechts Bössor is named Örsdöder (Destrier killer), Keterlin Haverblast, Faule Agnes and Mathilda.

The other guns are yet to be named.

This article, written by Johan Käll & Peter Ahlqvist, was previously published on our old webpage.