Background

After the war between Albrecht of Mecklenburg and Margareta (read more here), Albrecht and his son was imprisoned at castle Lindholmen in the region of Skåne in southern Sweden. In July 1394, after lengthy negotiations, it was agreed that the two Mecklenburgers should be set free for a ransom of an immense sum of money, equivalent to about 8 000 kilos (more than 17 600 lbs) of pure silver. In short, they were to be released for three years, in which they had to come up with the money, and the city Stockholm was to act as a kind of deposit. Stockholm was the only city in Sweden still controlled by the Germans and hence a thorn in Margareta’s side. During those three years, Stockholm was to be superintended by a group of Hanseatic cities (Königsberg, Elbing, Thorn, Danzig, Reval, Greifswald, Lübeck and Stralsund), as the cities had agreed to act as guarantors for Albrecht. For their troubles, Margareta should pay them an annual sum of 2 000 mark for the three years they administered Stockholm. Also, the cities Rostock and Wismar (the heartland of the Mecklenburg dynasty) should help out with considerable sums of money – 1 000 mark per year.

The mission

Preparations

The 20th of May 1395 the cities met in the neighboring fishing towns Skanör and Falsterbo, at the southwesternmost tip of Sweden and they agreed about their respective contributions to the mission, in wider terms. Here, they also came to terms with Margareta that the king and his son Erich were to be set free the 29th of September. It was agreed that Greifswald, Stralsund and Lübeck should send half of the personnel, equipment and provisions needed. The Prussian cities (the five remaining of the eight) should send the other half.

As an aside, 1395 is a year where the so called Vitalian brotherhood (a group of pirates) starts to take up more and more of the Hanseatic League’s agenda; in September it is decided that a peace keeping/pirate hunting fleet consisting of 11 ships and 1 000 men at arms is to be set up until 1396 to address the piracy problem. 1396 the pirates are mentioned in almost every meeting held by the Hanseatic League, which gives an impression of the situation in the Baltic region.

The Skanör-Falsterbo agreement above states that the eight cities in total should send the following personnel and equipment to take control of Stockholm:

- 80 good men at arms in full armour (in this case this included torso protection other than chainmail)

- 60 good crossbowmen with their weapons and including equipment

- 12 barrels of crossbow bolts

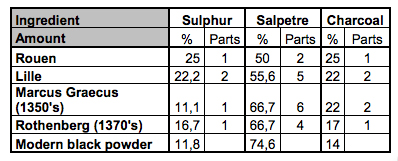

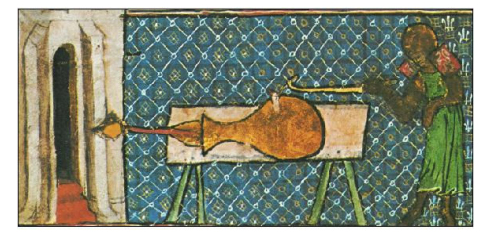

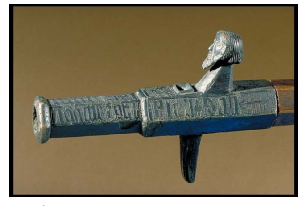

- 8 stone guns (bigger cannons)

- 2 lead guns (smaller cannons/hand guns)

- “A lot of gunpowder, which is needed for that” [the guns]

- 60 good crossbows including levers and windlasses

- Two good gunnery masters

- Two crossbow makers

In addition, the cities sent large amounts of food; in short, everything that was needed to survive was to be shipped to Stockholm, including different food stuffs and tools.

About two months later, in the middle of July, the cities met in the Teutonic order castle of Marienburg/Malpork, where more exact guidelines for the mission are drawn. The troops shipped to Stockholm from the Prussian cities (Königsberg, Elbing, Thorn, Danzig, Reval) are:

- 38 men at arms

- 22 crossbowmen

They bring

- 8 guns of different types, including powder, lead for making shot and peripheral equipment

- 1 gunnery master

- 1 crossbowmaker

- 30 crossbows

- 4 barrels of crossbow bolts

- Peripheral equipment for the crossbows

The soldiers

Personal equipment

In the Marienburg meeting it was stipulated that each soldier should be equipped according to the following lists:

Each crossbowman should have:

- 60 good bolts with tips

- 3 crossbows (!) – one big, one middle sized and one small

- A chainmail

- A “chest” – probably a coat of plates

- A mail coif

- A iron hat

- Plate gauntlets

- A shield

Each man at arms should have:

- A “whole plate armour and what belongs to it”:

- A hood (most likely a helmet)

- A coat-of-plates

- Arm protection made of leather

- A “vorstal” – probably lower arm protection made of steel

- Leg protection

- A shield

Curiously, nothing is mentioned of which weapons a man at arms should bring. Perhaps it didn’t matter, as long as they were armed. I have found no similar lists for Stralsund, Greifswald and Lübeck, but most likely those cities sent a similar number of soldiers with similar equipment.

Loyalty

The soldiers going to Stockholm had to swear a sacred oath when signing up for service:

Dys yst der wepenere unde schuczen yet unde buchsenmeystere unde bogenere. Wir sweren und geloben uch, borgermeisteren, ratmannen unde der ganczen gemeyne der stede Thorn, Elbing, Danczik unde Revele, daz wir hern Hermanne van der Halle, euwirme houbtmanne, und unsern eldesten getruwe und gehorsam will zin in bewarynge, in wache, in were des huses, veste und stat Stokholm, unde in alle anderen dingen, des uns van in bevolen wirt; unde van dannen nicht to scheydende, ee ir uns orlob gebit unde andere in unse stat sendit. Das en wille wir nicht lassen durch lib noch durch leyt, daz uns Got zo helfe unde dy heylighen.

This is roughly translated into:

This is the oath of the men at arms, the crossbowmen, the gunnery masters and the [cross?]bowmakers. We swear and promise you – the mayors, the council and all the common people of the cities Thorn, Elbing, Danzig and Reval, that we will be true and obey herr Hermann van der Halle, our noblest commander, when it comes to guarding and caring for the houses, castle and city of Stockholm, and in all other things he will command us; and therefore not to let anyone in [to Stockholm] without permission, in good times or in bad, so help us God and the Saints.

Pay, benefits and conditions

The tour of duty for the soldiers going to Stockholm was to be 18 months long, as suggested by a meeting the 19th of August, 1395.

The soldiers from the Prussian cities were paid both in fabric and in money. The men at arms was to be paid in 6 ells (1 ell = nearly 60 centimeters) of black and brown fabric (probably 2 ells wide) from Dendermonde (in Flanders), from which they should make “wide coats and hoods”, where the black should be on the right side and the brown on the left. The crossbowmen should have hoods in the same colors, plus parcham (a fabric consisting of both linen and cotton) for their jacks/gambesons. The pay also consisted of 5 marks in coin per year for the crossbowmen and 10 marks per year for the men at arms. It is not clear whether similar conditions applied to the contingents from Stralsund, Lübeck and Greifswald, even though it is probable.

In excess of this, the soldiers would probably have had free food, drink and lodgings. But like always, it seems the pay for the contingent was too little and too late. In comparison to other missions (i.e. on peace keeping ships) the pay wasn’t exactly good. In April 1396 a League meeting in Marienburg states that men at arms that goes on the peace ships without their own armour shall have 1/3 of one Mark each week. If we presume that the peace keeping mission lasted for a year (which it probably didn’t), the participating men at arms would earn more than 50% more per year than their colleagues in Stockholm. On the other hand, the peace keepers didn’t receive any fabric, but this doesn’t cover the difference.

That might be why the superior commander of the Stockholm mission, Hermann van der Halle, made complaints about “uncomfortable” individuals in the force; it could have something to do with the talks at a League meeting the 31st of December, 1396, where the gathered representatives decide to postpone the question of “pay for the men at arms that have been posted in Stockholm this year” to an upcoming meeting.

Food

It seems the garrison commander had trouble making ends meet. Van der Halle sent frequent letters to his superiors asking for the most basic commodities to be shipped from Germany, which indicates the contingent couldn’t easily get hold of locally produced food; for some reason the force couldn’t even use the mills in Stockholm and had to grind their grain to flour via a hand mill.

This, among other things, were ordered from Germany to be delivered to the garrison: Apples, honey, onions, beer, pork, many different kinds of fish, bread, turnips, vinegar, salt, mustard, different kinds of oil (which could also have been used as fuel for lanterns), flour, malt, hops, peas, horseradish, apples and garlic.

Among the finer foods (probably reserved for the commanders) can be found: rice, almonds, raisin, wine and spice.

The posting

Arrival

The contingent, commanded by the Danzig council member Hermann van der Halle, who was appointed supreme commander of the mission, reached Stockholm and took control over it the 31st of August, 1395. The day after that, the commander of the Stralsund contingent, Magnus von Alen, arrived in Stockholm with his men. Lübeck also seem to have sent a commander – Jordan Pleskow (who maybe rather wanted to stayed at home in his house on Johannisstraße 20 in Lübeck – we’ll never know). A week later, the 8th of September, the cities promised the Stockholm burghers the same freedoms as they had under the reign of King Albrecht, and the burghers – in turn – promised to be true to the trustees responsible to administer the pawned city.

The keepers of the castle, which consisted of Albrecht supporters, among others Hinrike von Brandis and Otto von Peckatel, had been informed of the turning of the tide beforehand; the Hanseatic League wrote them a letter a month before van der Halle and his troops arrived in Stockholm. Von Brandis and von Peckatel handed the city over to van der Halle without much of a fuss.

We are presented with information that paints a picture of Stockholm castle in disrepair, and probably the soldiers were put to work to repair everything, including the lodgings that had been built by private persons in the castle. The inhabitant of said lodgings – the duke Johann von Mecklenburg (a relation to King Albrecht) asked van der Halle’s permission to remain, something he was denied.

The soldiers had nevertheless to undertake what was most likely extensive renovations; the walls and roof of the castle was in a sorry state, and the cities demanded that the renovations were kept cheap. Also, the old castle commander “borrowed” a lot of kitchen equipment and a stone gun, which needed to be replaced. To assure that the borrowed gun shouldn’t be used against the castle by the leaving force, van der Halle decided to buy it from the leaving Albrecht supporters.

A less than desirable task

Hermann van der Halle didn’t seem too happy with his task. His letters back to his superiors are full of new requisitions as the victuals always ran out. Already the 19th of September, 1395, the council of Marienburg addressed van der Halles requisition for onions, garlic, herbs, fruit, honey, cod, beer, wine – and “6 or 8 big hounds, that we need so well for the castle”. Seven days later the council at Marienburg addressed a second requisition of malt, barley, more beer and wine, flour, fish, vinegar, onions, more dogs, two big ships to defend against the Vitalian brotherhood, wooden boards, (lots of) shovels and brick trowels.

In June 1396 we learn that Stockholm castle had been divided between the Stralsund forces of Magnus van Alen and the forces of Hermann van der Halle, where the Stralsunders were using the tower for their needs and the other troops occupied the courtyard (probably in the buildings erected by duke Johann von Mecklenburg) plus a cellar belonging to the keep, as they had agreed on that this was the best way to defend the castle.

Risky business

However, it seems the stay in Stockholm wasn’t only hard work; the Vitalian brotherhood was increasingly seen in and around the city – both as visitors (even as guests of the Stockholm council during wintertime, something that worried van der Halle) and as pirates. In April 1396, the cities asked van der Halle to send what troops he could spare to the peace keeping mission against the brotherhood being set up by the League.

In June he reported that ”a good hundred” members of the brotherhood, that had spent the winter in Stockholm, finally set off for Russia under the command of eight commanders in eight freight ships and with ”gunner boats”. Van der Halle made them promise not to go after the Hanseatic merchants or cities in Livonia before they left.

In August the same year, van der Halle reported several incidents involving the pirates and merchant sailors; the situation was clearly becoming more and more dangerous for the Stockholm detachment.

Furthermore, some things indicate that the commander didn’t quite trust all of his men, as he asked his superior’s permission to send some of them home: ”if they don’t please me, I want to [be allowed to] tell them: ’Go home!'”.

It seems Hermann van der Halle was also worried about the agents of Margareta; the queen invited him to meetings several times during 1396, but he never left his post. Even when the queen sent her envoy, Sten Bengtsson, to visit Stockholm, he had to announce his visit some day ahead to be let inside the gates. The queen’s envoys also demanded (according to their view of the peace treaty) that he should open the gates to 300 Swedish burghers that had been banished from the city due to their lacking loyalty to King Albrecht. Van der Halle asked his superiors for orders concerning this, but had a hard time stopping the said burghers from coming and going to the city.

By this, we can assume that the soldiers of the League was in a constant state of readiness.

Relief

Hermann van der Halle’s successor, Albrecht Russe, arrived in Stockholm in the beginning of October 1396, accompanied by an experienced old fighter and diplomat, sent by the Elbing council. His name was Claus Wulf and he had commanded soldiers since at least 1386. Likely he was sent to command the Elbing contingent, under the command of Albrecht Russe. Russe assumed command over the garrison and no sooner, Hermann van der Halle borrowed 100 marks from Russe and left in the first ship available. More than a year later he is still struggling to get the League to pay him what it owed him for his expenses in Stockholm.

If Albrecht Russe thought he would have an easy time, he was mistaken. He had to deal with the same troubles that pestered van der Halle. He hadn’t enough men, although he had too much men to feed them properly, he had to address the issue with “uncomfortable” and probably bored and restless personell and he was working at a place where he was less than welcome by the populace and by the pirates.

However, he seems to have had his ear to the ground, as he picked up a subtle warning about events waiting to occur during the summer of 1397. When commanding Stockholm castle, Hermann van der Halle had feared that a Swedish nobleman named Algot Magnusson had struck some kind of a deal with the Vitalian brotherhood. His fears seems not to have been ungrounded, as a man came to Russe, warning him of an imminent danger. The 28th of June, a big fleet of the brotherhood arrived in Stockholm, issuing demands. One can imagine the commotion in the castle when the 100 or so soldiers at some hours notice tried to ready the defenses against a force that was 1 200 men strong. Later, Russe told his superiors that he and his men had been nowhere close to ready or strong enough, and that the city would have fallen if the brotherhood had attacked.

In January 1398, Russe complained that Margareta didn’t send money for the upkeep of Stockholm, as agreed. At the same time he asked for provisions (as always) and to be relieved of his post the upcoming easter. In the agenda of a late February League meeting the participants urge that Rostock and Wismar should pay what they owe for the keeping of Stockholm. Money was, as usual, a problem.

In May 1398 a meeting at Marienburg decided that every city involved in the mission should send 3,5 Mark worth of victuals per soldier from the city in question – a grand total of 300 Mark. This is a bit interesting as it gives us an approximate number of the garrison. At this time it seems the force in Stockholm was about 85 men strong. Maybe some of the ”uncomfortable” elements were sent home?

After this, the annals of the Hanseatic League doesn’t mention the Stockholm garrison much. The times Stockholm are mentioned, it is regarding its surrender to Margareta.

Aftermath

During the spring of 1398, Margareta corresponds with the cities about her accession of Stockholm. The 12th of August she states that if King Albrecht hasn’t payed his ransom by the 24th, she will ask him to surrender Stockholm to her. The 29th of August, she – along with her son Bogislav (now king of Sweden) – grants Stockholm all of its previous rights; as history tells us, the king couldn’t come up with the money. The contingent from the Hanseatic League leaves the city the 29th of September and Margareta takes over. The mission is accomplished and the soldiers return home – or sets off to find the next filled purse, perhaps as part of the ever ongoing war against the Vitalian brotherhood.

The supreme commanders from Prussia

Hermann van der Halle

When the cities’ troops first arrived in Stockholm – in August 1395, they were supervised by the Danzig council member Hermann van der Halle, as mentioned above. He was sworn in as hovetman the 1st of August, where he specifically asked that his mission as commander over Stockholm should last no longer than a year.

He had the responsibility to keep Stockholm safe, which was easier said than done. Hermann van der Halle’s letters often include reminders to his superiors that he was promised to be relieved of his post after one year; it is clear that he is not very happy in Stockholm. Maybe it had something to do with the people he was forced to work with; in July, 1396 he thanked his superiors for the long asked for permission to send “uncomfortable” individuals home. Probably he was referring to members of the Thorn contingent – he made complaints about them at a League meeting in March 1397.

The 15th of June 1396, his supervisors sent him an eagerly awaited letter – he was to be relieved – as promised – by the Thorn council member Albrecht Russe. The 3rd of September he seemed somewhat anxious to learn that Russe had fallen ill in Lübeck. In the end of the same month, van der Halle himself fell ill, and as he experienced that he was of no use to the garrison, he desperately asked his superiors to send another commander as soon as they were able.

He seems to have pulled through, though, as he was present at a League meeting in Marienburg, the 31st of December, 1396.

Albrecht Russe

The Thorn council member Albrechts Russe (or “Albrecht Rusze” as he spelled it himself – an indication of his perhaps Russian descent) was appointed council member of Thorn 1393. This might well have been his first commission, where he acted as a representative for the city at various League meetings. During his career he also acted as a bailiff, mediator and solicitor, as well as councillor and mayor in the same city. He acted as a diplomat during various diplomatic postings, and was probably also a shipowner responsible for Thorn’s trading relations with Poland. A heavy weighter, no doubt.

In 1396 it is decided that he is to succeed the commander of the Stockholm garrison, Hermann van der Halle. The 14th of September 1396, Russe sends word that he plans to depart from Wismar to Stockholm the 29th of September. It is probable that he arrived in Stockholm less than a week later, which means his predecessor could take the first boat home and the heck out of Dodge during the first days of October.

Russe assumed command at the most critical period of the Hanseatic administration of the Swedish capital. The evening of the 29th of June, 1397, a fleet of 42 ships and 1 200 men, commanded by “Otto von Peckatel [former commander of the Stockholm garrison], Sven Stur, Crabbe, Egkart Kale, Kawle and other commanders that I do not know” reached Stockholm. It was a fleet belonging to the Vitalian brotherhood. It had sailed from Gotland where King Albrecht’s son Erich had put up his headquarters, along with several notable nobles – among others the duke Johann von Mecklenburg who was evicted from his house in Stockholm castle in 1395. This means that Erich von Mecklenburg took active part in the piracy that Margareta, the Teutonic order and the Hanseatic league was trying to thwart, even though he was released on bail. Perhaps this was his way to raise money for the ransom. Either way: talk about stirring the pot…

Russe sent a letter to his superiors recounting what had taken place that evening. Its contents were read out and addressed at a League meeting in Danzig the 2nd of July, three days later.

The two sides met at a small isle outside Stockholm to parlay. The fleet commanders demanded to be let inside the city, but the officials of Stockholm refused. The fleet then demanded 10 000 loaves of bread and 20 “last” (= 200 plus barrels = more than 43 000 liters) of beer. The commanders of Stockholm refused a second time, and the fleet commanders asked to buy the commodities they needed. Again they are refused; the Stockholm officials suspected treason as Albrecht Russe had received a warning some time earlier.

He tells his superiors:

A good man came to me and told me to guard the castle well – or be in dire hardship. Then I told him: ”My dear friend, can’t you speak your mind?” He said that he couldn’t tell me. He kneeled, and put two fingers on a brick, and spoke thus: ”Brick! I tell you this, as God and the Saints help me: Stockholm is betrayed!” He rose and reached his arms towards the sky and spoke: ”So help me God until my last day – what I have sworn here is the truth!” He would tell me nothing more.

After this, Russe asked for more provisions and reinforcements (“good people”) as he believed Stockholm to be in real danger. However, the fleet departed and left Stockholm alone. The League responded by ordering that one of the gates in Stockholm should be walled shut, perhaps as part of the defenses against the brotherhood.

Like his predecessor, Albrecht Russe constantly asked to be relieved, which makes you wonder what kind of a place Stockholm was. In late summer 1397, the League sent him a letter and told him that he, in time, was going to be relieved from his post by a representative from Elbing. It is uncertain if he ever was relieved or if he remained on his post until the mission in Stockholm ended.