Winds of war

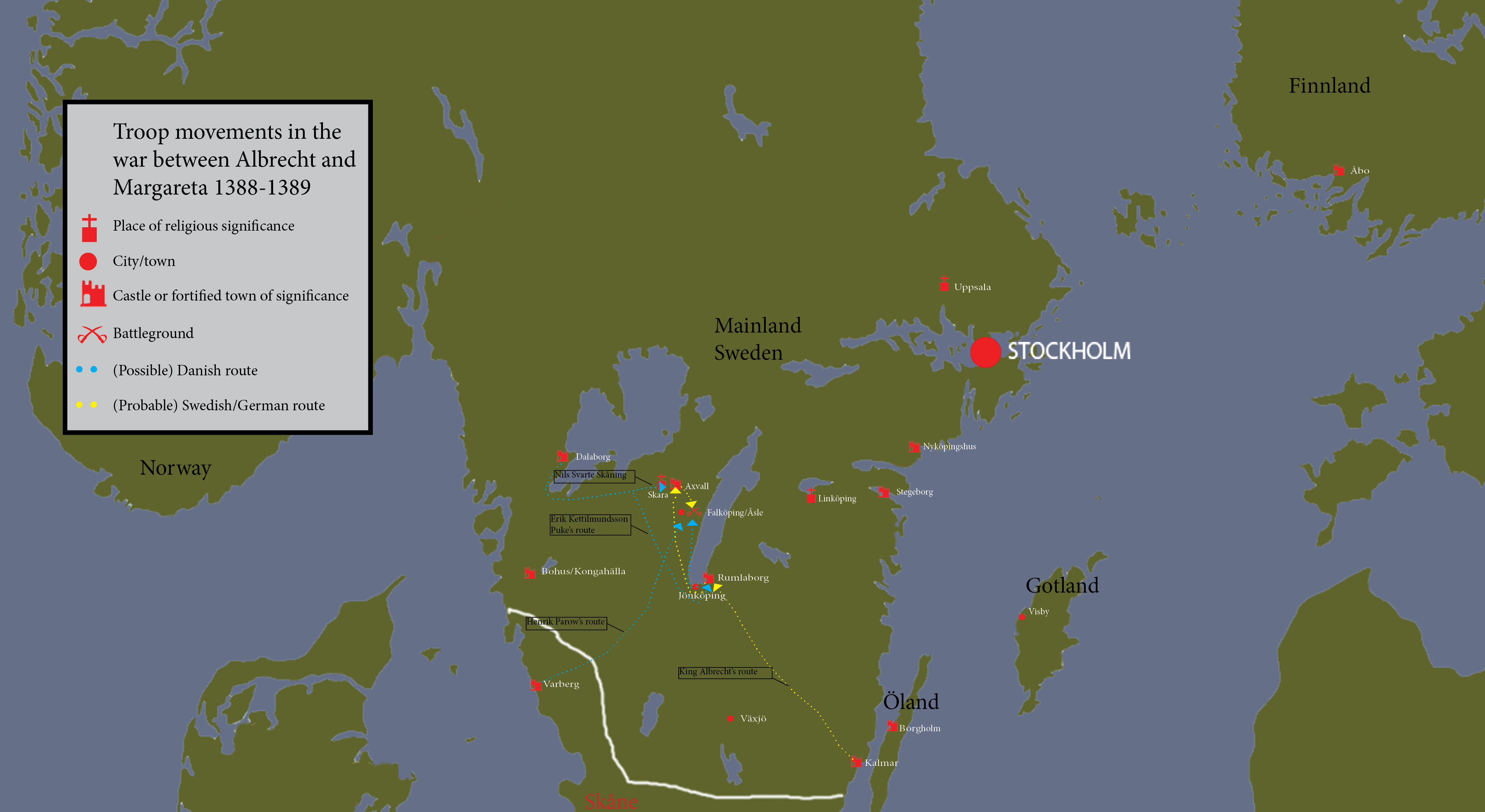

After the meeting at Dalaborg, Margareta starts to gather an army to fight the king, But Albrecht is not sitting idle. He makes the burghers of Stockholm renew their oath of fealty to him and departs for Germany to muster troops. Margareta is ahead of him, and with an army of Swedes her supporters besiege the stronghold of Axvalla. It is too strong to take by storm, and a long siege lead by Nils Svarte Skåning begins. The main part of the army marches on, under the command of Erik Kettilsson Puke (whose name has got nothing to do with throwing up).

Around new year 1389 Albrecht returns to Sweden with a host of men. He disembarks at Kalmar and march on Axvall. On the way there, he passes the south peak of lake Vättern, and manage to liberate the besieged Rumlaborg. When he reaches Axvall he also receives word that a Danish army, under the command of his old retainer Henrik Parow has been marching from Halland and is about to join the army of Erik Kettilsson Puke. Albrecht turn south to face the two armys, and the 24th of february they meet outside the village of Åsle, in the vicinity of Falköping.

The chronicler Detmar describes it like this:

In deme jare Cristi 1389, in sunte Mathias dage, was grot strid in Sweden bi Axewalde. De koninghinne van Norwegen hade dar sand wol vifteynhundert gewapent. Der hovetman was en riddere, de heet her Hinrik Parowe.

On this day of Christ 1389, in saint Matthew’s day, it was a great battle in Sweden by Axvall. The queen of Norway had sent a good fifteenhundred armed. The commander was a knight that was called Henrik Parow.

Henrik Parow’s troops take a defensive position flanked by a mountain and a marshland, which also stretches in front of his lines. Albrecht is eager to engage, and he is certain of victory; his host consists of glorious German knights and trained mercenaries. But everyone is not as sure as he is. Tradition tells us that an old knight called Tyke Olofsson asked the king to refrain from attacking, or at least try to negotiate the marshland before charging. ”We do not want to fight the Dane this day – it won’t do us any good.” he concluded, but the king wouldn’t listen. Even though some of his men weren’t ready, he lead his knights, including the bishop of Skara, his cousins and the counts of Ruppin and Holstein, on a charge across the frozen land and at first he was very successful: he ”conquered two banners”. But the battle would not go his way. One of his commanders, Gerhard Snakenborg, turned and fled the battlefield with 60 riders, and others is said to have stuck in the boggy ground.

In less than two months, through snow and during very harsh conditions, king Albrecht’s army marched over 300 kilometers – and had time to stop and liberate Rumlaborg before fighting at Åsle

The king was taken captive along with his son, prince Erich, and as they were taken from the field of battle by their captors, they passed Tyke Olofsson. The king cried out to him: ”Old man! Old man! Why didn’t I listen?” The battle of Åsle is a decisive victory for the rebels, but their commander, Henrik Parow, is killed. When the queen learns of the victory she rides to Bohus where she and her supporters celebrate their victory. The king and his son are eventually taken to Skåne and the castle of Lindholmen, where they are being held captive.

German resistance

Even though Margareta managed to beat her enemy at the battlefield, her fight for dominion of Sweden was far from over. Although she conquers Kalmar, Rumlaborg and Axvall, Stockholm is still in German hands, and the burghers of the city refuse to give up the fight. They are being supported by the Hansa, which send warships to commandeer ships belonging to the supporters of Margareta. They also bring food and soldiers to the besieged Stockholm. On a different note, these ships, crewed by knights, burghers, soldiers and peasants, according to Detmar, later cause much trouble on the Baltic sea as pirates (so called Vitalianer). As they are allowed to enter the harbours of the Mecklenburgish Wismar and Rostock, other Hansa cities, which suffered economic losses due to pirate attacks, started to lose interest in the conflict between the Mecklenburgish dukes that supported Albrechts and the queen Margareta. Nevertheless, some of the Hanseatic towns, Rostock among some others, make alliances with noblemen and other cities to try to force Margareta into releasing Albrecht; among other things they try to enforce a trade embargo against Margareta. But their efforts are of little use. Some, like the old Albrecht-loyal knight Vicke van Vitzen even sells his estates to Margareta and swear loyalty to her. He was not the only one to do so.

The aggressive Vitalianer pirates put a hamper on trade in the Baltic sea. Many ships were just anchored as the risk of sailing was too great

In 1393 the conflict is putting a big hamper on trade in the Baltic sea, not least because of the Vitalianer. Margareta met with representatives from the Hansa and king Albrecht’s nephew Johann in Falsterbo at the end of September. At this meeting it was agreed that Albrecht and his son should be let free from captivity for a couple of years, until the parties had reached an acceptable agreement. As security, the city of Stockholm was to be handed over to four honest men, which should let Margareta occupy it if the king refused to go back to captivity after the said time.

The war goes on – but so does the negotiations

In July 1394 everyone finally seemed to agree. The king and his son had been imprisoned for more than five years, and the king himself probably knew that his days as king of Sweden were numbered. He was to be released against a huge ransom of 60 000 marks of silver (the old king Magnus bought the entire province of Skåne for about half as much in the 1330’s), and if that sum wasn’t paid back in six months, the king and his son should return into captivity, or the queen would be entitled to occupy Stockholm. At the same meeting, Margareta and the Hansa also agreed on taking actions against the Vitalianer, as they were still a serious problem for great parts of northern Europe. During the 1390’s tremendous efforts were put on ridding the Baltic sea from pirates. Several fleets with several thousand men hunted the Vitalianer and drove them from whatever harbors the controlled.

The final negotiations for the king’s release took place at Lindholmen were king Albrecht and his son had been spending their time since the defeat at Åsle. The 26th of September 1395 it is decided that Albrecht and his son should be released for a period of three years (until the 29th of September 1398), during which time they should try to raise the enormous ransom. If he succeeded, he wasn’t allowed to wage war on Margareta for at least a year. If he didn’t succeed, he could go back to prison but break the peace in nine weeks, or he could simply let Margareta have Stockholm and the peace should be everlasting. Albrecht was released in Helsingborg at the end of September 1395, about a month after Stockholm was entrusted to the Hanseatic cities (read more here) of Königsberg, Elbing, Thorn, Danzig, Reval, Greifswald, Lübeck and Stralsund, as a kind of peace keeping force, while Albrecht and Erich started to round up the money needed for the ransom. Their efforts was however in vain, and in 1398 the cities’ representatives leave Stockholm, allowing Margareta to occupy the city. The conflict between king Albrecht and Margareta is definetely over.

Today the castle of Lindholmen is nothing more than a grassy mound, but in the 14th century it was one of the most important castles in the entire Danish realm

A free man

Albrecht returned to his Mecklenburg of old and ruled the land for years. In a letter dated 25th of November 1405, in the end, he was able to forgive the peoples of Sweden, Norway and Denmark for what evil they had bestowed upon him. The same date he also writes other letters, in which he states that he will no longer claim Swedish regions, but rather support his son, duke Erich. Albrecht dies 1412, and with him dies the Mecklenburg dynasty’s hopes for the Swedish throne.

Margareta, Bogislav and the Kalmar union

Margareta, her adoptive son Bogislav, the Swedish council and many other Swedish nobles were gathered in 1396 to the recess of Nyköping, which in short meant that the crown reclaims all estates and all land that has been given or claimed since 1363, when king Albrecht came to power. All strongholds an castles that was built during those years should be torn down if the queen so wished. But that wasn’t all that was discussed. The most important thing at the meeting was that the congregated potentates agreed that none of the three Nordic realms should wage war on oneanother. They had ”in all these kingdoms one lord and king”. The young Bogislav of Pomerania could look forward to a splendid position as king over a great realm.

He was crowned in 1397, and at the same time the Kalmar union was signed between the three kingdoms. The statutes of the union stipulated, among other things, that the descendants of the king should inherit the crown – a direct dichotomy to the Landslag, accepted in the middle of the 14th century. Also, each country should have right to their own laws, but at the same time they should henceforth be seen as one kingdom – under ine king. Margareta was still holding the reins until 1400 when Bogislav came of age and at least formally took over power from his mother. He reigned the new union between 1400-1439 with two interludes. He was however forced to change his name into the more proper Swedish name Erik – Bogislav was too strange a name for the Scandinavians.

1400 Erik came of age, and rode his Eriksgata the following year, but his mother was still holding most of the power; she was in no way willing to let go of her influence.

In 1402 Margareta negotiated with Henry IV of England to be able to marry Erik with Henry’s daughter Philippa. The negotiations went well, and Erik and Philippa was married in Lund 1406.

He, his young queen and his mother worked hard to strengthen the three kingdoms against first and foremost the Germans, in the form of the Hansa and the Teutonic order. Their measures included instating foreign vasalls to control Sweden, which eventually lead to unrest amongst the population.

Before that, however, they declared war in the Hansa, as they considered the trade confederation too powerful. On the side of the Hansa, the Holsteiners joined, and the Baltic region was thrown into a war that lasted until 1435, with some armistices.

Margareta died the 28th of October 1412, when negotiating for the city of Flensburg, which had been seized by the Holsteiners. She is buried in a magnificent sarcophagus in Roskilde cathedral in Denmark. Curiously enough, king Albrecht died the same year, the 31st of March or 1st of April. He was laid to rest alongside Richardis in the Doberaner Münster in Bad Doberan of the Mecklenburg area.

This article was written by Peter Ahlqvist.